Newsom signs first-in-nation law to ban ultraprocessed food in school lunches

California health officials will now decide which ingredients, additives, dyes, and other forms of processing don’t belong in school meals and K-12 cafeterias.

This story was originally published by CalMatters. You can sign up for their newsletter here.

California is the first state in the country to ban ultraprocessed foods from school meals, aiming to transform how children eat on campus by 2035.

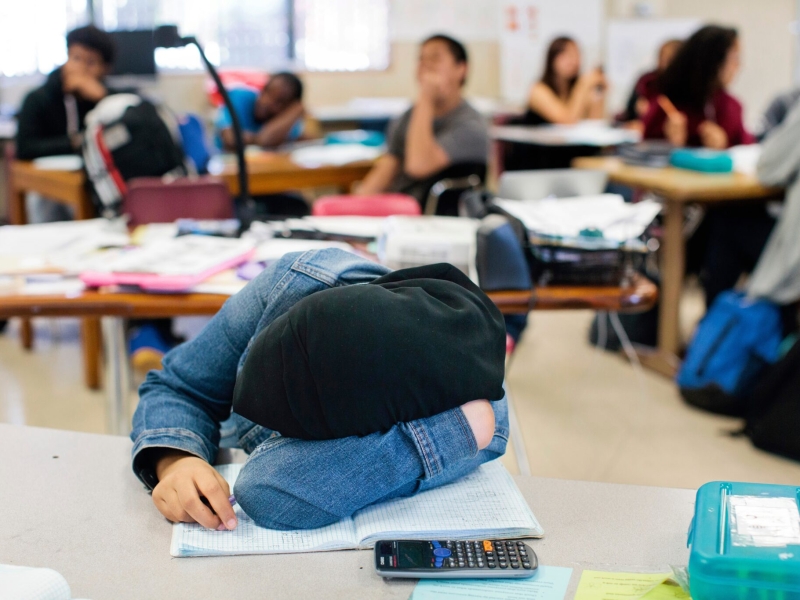

In the cafeteria of Belvedere Middle School in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Boyle Heights, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a measure that requires K-12 schools to phase out foods with potentially harmful ultraprocessed ingredients over the next 10 years. The requirements go above and beyond existing state and federal school nutrition standards for things like fat and calorie content in school meals.

California public schools serve nearly 1 billion meals to kids each year.

“Our first priority is to protect kids in California schools, but we also came to realize that there is huge market power here,” said Assemblymember Jesse Gabriel, an Encino Democrat. “This bill could have impacts far beyond the classroom and far beyond the borders of our state.”

The legislation builds on recent laws passed in California to eliminate synthetic food dyes from school meals and certain additives from all food sold in the state when they are associated with cancer, reproductive harm and behavioral problems in children. Dozens of other states have since replicated those laws.

The bipartisan measure also comes at a time when U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.’s “Make America Healthy Again” movement has shone a spotlight on issues including chronic disease, childhood obesity and poor diet.

The term “ultra-processed food” appears more than three dozen times in the MAHA report on children’s health released in May. A subsequent MAHA strategy report tasks the federal government with defining ultraprocessed food.

California’s new law beats them to the punch, outlining the first statutory definition of what makes a food ultraprocessed.

It identifies ingredients that characterize ultraprocessed foods, including artificial flavors and colors, thickeners and emulsifiers, non-nutritive sweeteners, and high levels of saturated fat, sodium or sugar. Often fast food, candy and premade meals include these ingredients.

Researchers say ultraprocessed foods tend to be high in calories and low in nutritional value. Studies have linked consumption of ultraprocessed foods with obesity. Today, one in five children is obese.

Ultraprocessed foods are also linked to increased cancer risk, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Studies have found sweetened beverages and processed meats to be particularly harmful, said Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist at the Environmental Work Group, which sponsored the legislation. Kids are particularly susceptible to the effects of ultraprocessed foods, she said.

“Ultraprocessed foods are also marketed heavily to kids with bright colors, artificial flavors, hyperpalatability,” Stoiber said. “The hallmarks of ultraprocessed foods are a way to sell and market more product.”

Gabriel said lawmakers and parents have become “much more aware of how what we feed our kids impacts their physical health, emotional health and overall well-being.” That has helped generate strong bipartisan support for the law, which all but one Republican in the state Legislature supported.

A coalition of business interests representing farmers, grocers, and food and beverage manufacturers opposed it. They argued the definition of ultraprocessed food was still too broad and ran the risk of stigmatizing harmless processed foods like canned fruits and vegetables that include preservatives. Vegetarian meat substitutes also generally contain things like processed soy protein and binders that may run afoul of the definition.

Gabriel contends that the law bans not foods but rather harmful ingredients. The California Department of Public Health now must identify ultraprocessed ingredients that may be associated with poor health outcomes. Schools will no longer allow those ingredients in meals, and vendors could replace them with healthier options, Gabriel said.

Supported by the California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), which works to ensure that people have access to the care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Visit www.chcf.org to learn more.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Through December 31, NewsMatch is matching donations dollar-for-dollar up to $18,000, giving us the chance to double that amount for local journalism in Shasta County. Don't wait — the time to give is now!

Support Scout, and multiply your gift