“Golden Ghosts” Shares Black Californians’ Remarkable Journeys To Freedom During The Gold Rush

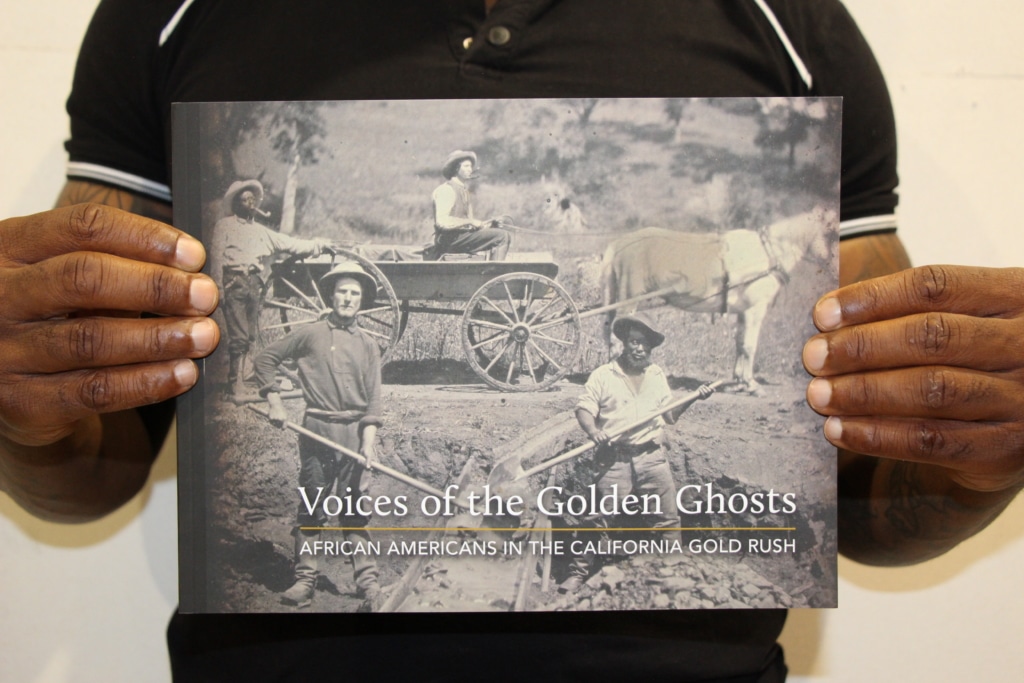

Long romanticized as an era of unbridled freedom, migration and entrepreneurial spirit, California’s Gold Rush was also a time of enslavement and hateful racial violence. In a new book titled Voices of the Golden Ghosts, a collective of North State authors reveals the fascinating 19th century Black Californians who fought against systemic discrimination in sophisticated ways to free themselves from bondage and establish a sense of belonging in their new home.

Updated 10 a.m. March 5: This story has been slightly revised to clarify the source of a historical anecdote.

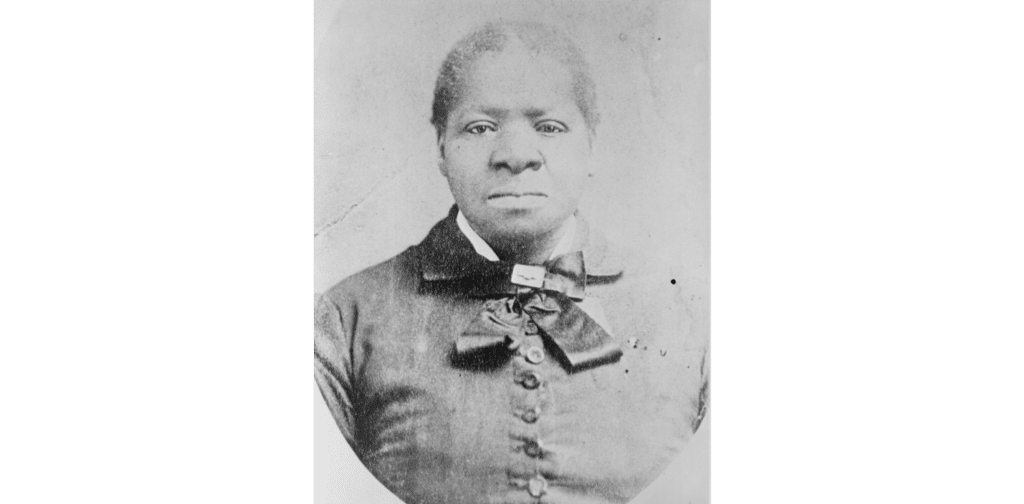

In the early 1850s, a Mormon tenant farmer forced Bridget “Biddy” Mason and other enslaved Black people he owned in Utah to migrate by foot more than 800 miles across state lines to California.

California had recently joined the United States as “free soil,” so Mason was legally emancipated as soon as she crossed the border. But her enslaver flouted that law, claiming Mason and the other enslaved Black people under his control wanted to stay with him because they were “like family.” As a result, Mason was liberated from the farmer’s bondage only after free Black people with significant influence were able to successfully lobby a court with a sympathetic judge to intervene.

She used her freedom to become a licensed doctor’s assistant before eventually founding her own private practice as a nurse and midwife in Los Angeles. Through careful saving, she accumulated significant wealth, which she used to provide affordable housing, a daycare center, and disaster aid for the Black community around her.

Mason’s story is one of several powerful narratives featured in the recently released book Voices of the Golden Ghosts, an 82-page illustrated volume that includes several essays by North State writers.

Golden Ghosts reveals a different side to the Gold Rush, an era that’s long been associated with unbridled freedom, widespread migration, and entrepreneurialism. In chronicling the lives of 19th century Black Californians, many of whom arrived in the state as slaves, the book punctures the myth of the Gold Rush as a time of free-wheeling adventure during which intrepid migrants sought an escape from poverty and the promise of fortune. It also challenges the historical misconception that slavery was confined to the South.

The book’s authors don’t soft-pedal the grim realities Black people experienced during the Gold Rush, including illegal enslavement, lynchings and the terrifying kidnappings of so-called “fugitive slaves.”

But they also honestly portray Black Californians as victors, powerful people who took extraordinary measures to escape slavery and make California a place of belonging. It was no law or proclamation that freed slaves, the book’s essays make clear, but the actions of enslaved people who took enormous risks to free themselves.

Remarkable freedom stories like these have long been marginalized in Gold Rush histories, which is one reason why Redding resident Celeste McAllister, who grew up in the same L.A. neighborhoods where Mason once lived, had never heard of her.

McAllister learned of Mason when she joined the largerVoices of the Golden Ghosts project in 2019, which began as a series of staged performances in which Black North State community members took on the roles of these Gold Rush historical figures.

Organized by North State filmmaker Mark Oliver, Voices of the Golden Ghosts is an ongoing project that excavates the neglected histories of Black Californians during the Gold Rush through performances, museum exhibits, and other media. The book is the latest iteration of the project, and Oliver said they are now working on bringing the Golden Ghosts program into local schools.

Several Shasta and Siskiyou County African-American residents, including McAlister, have participated in the performances and also contributed to the book. After being asked to research Mason and perform a monologue as her, McAllister said she was stunned that she had never heard of this important historical figure who continues to fascinate her.

“(Mason) could have been so bitter for what she went through, but instead she was a nurturer and a caregiver. She birthed children of all colors as a midwife. She didn’t discriminate at her daycare,” McAllister said. “Her story makes me wonder what would have happened if all (enslaved) people had been free to follow their dreams and reach their full potential.”

McAllister, who is a youth tutor at the Martin Luther King Jr. Center in Redding, wishes she had been able to read the Golden Ghosts text as a schoolgirl.

“For her to rise above all of that is amazing to me. She shows you can’t stop a person who’s determined to do what they’re called to do,” McAllister said.

In addition to sharing biographical stories about Black people from the time, the book also explains how the practice of slavery was a prominent influence on early California politics, law, and economics.

Many believe that California was always intended to be a slavery-free state, Golden Ghosts contributor and Oregon State University historian Stacey Smith told Shasta Scout. But there was significant national disagreement on the topic. As white settlers moved West, many Southerners believed the area should become “a new frontier of slavery on the Pacific,” Smith says.

It was only after much political rancor that California entered the union in 1850 as “free soil,” with a constitution that banned slavery. And even then, the state’s nascent politics were largely dominated by former Southerners and others who were politically or financially invested in slavery, a group described in one 1863 newspaper article as California’s “slave oligarchy.”

In 1852, the influence of pro-slavery politicians also led the California government to pass the Fugitive Slave Law, modeled on the 1850 national Fugitive Slave Act; the law allowed settlers to maintain control over those who had been brought to California as enslaved people before it officially became a state.

While Smith estimates there were only about 500 to 1,500 Black people who experienced slavery during the Gold Rush, she says those numbers don’t necessarily capture the significance of California’s public and tacit support of slavery at a time when the tense national debate about abolition and slavery was ratcheting up.

“It was a big political statement to cooperate with the capture of fugitive slaves in an era when most free states were resisting this in the 1850s,” Smith said. “California is saying ‘not only are we not going to try to obstruct the Fugitive Slave Act, we’re going to pass our own and we’re going to side with slaveholders.’”

The book also details how some pro-slavery California judges and officials helped slave owners skirt the law. In practice, this meant that the roughly 5,000 Black people who lived in California during the Gold Rush faced widely divergent levels of freedom and bondage. Some came to California as free, others arrived as enslaved people, and even more faced discriminatory or exploitative labor conditions.

Reflecting this diversity, Golden Ghosts depicts a wide array of figures — from roaming abolitionists and ebullient saloon keepers to emigrant trail businessmen and midwives — who swiped freedom from the jaws of bondage. Many of the Golden Ghosts stories depict how enslaved Black people freed themselves by slyly navigating and resisting a system that was skewed against them

One of these figures is Alvin Coffey, who arrived in California from St. Louis while still enslaved. By mining gold around old Shasta City, a frontier town located five miles west of modern day Redding, Coffey managed to earn enough money to buy his own and his family’s freedom. He later started a school in Shasta City and donated the funds used to found a home for elderly African-Americans in Oakland.

Complicating some of the success stories of Golden Ghosts is the fact that free Black people like Coffey benefited from the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, including earning wages by participating in so-called Indian wars or purchasing property that was part of the stolen homelands of Native people who had been violently removed or murdered after living there for millennia.

Coffey, for example, joined the U.S. military in fighting the Modoc Wars, ostensibly an operation meant to violently erase Modoc people from their homelands to protect Euro-American settler society.

That’s one reason why Kyle Mays, a historian who authored An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States, advocates for a more nuanced investigation into the interwoven histories of Black and Native peoples, especially in cataclysmic eras like the Gold Rush.

Such examinations can also more fully explain the dynamics underlying historic encounters between Black and Native peoples. At times, especially when faced with limited choices for their own survival, they have been become enmeshed in each other’s oppression, but there have also been important moments of solidarity, he writes.

Smith, the Oregon State historian, captures some of this complexity in the opening vignette of her academic book Freedom Frontier, which tells the story of “Shasta,” a Yuki Indian child who was taken as a bonded servant by a federal Indian agent in the 1850s. Given the disruptive violence of the era, it’s most likely Shasta was captured after she had been orphaned as a result of massacres. But she was temporarily freed by a group of Black abolitionists who utilized the similar underground networks they employed to liberate enslaved Black people.

Her story illustrates how the early state of California established a legalized system to force Native people into various forms of bondage that included the kidnapping of Indian children to become household servants. Shortly before the California legislature legally supported the owners of enslaved Black people with the 1852 Fugitive Slave Law, politicians also passed in 1850 the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, a law which allowed local towns to sell captured Native people into what often became slavery under the guise of indentured servitude or “apprenticeships” for children.

Shasta’s story did not have a happy ending: she was eventually returned to the federal Indian agent because he had “legally” taken her as an apprentice.

Some of the historical Black figures in the Golden Ghosts book also faced struggles even after they were freed. But these stories are nonetheless redemptive, revealing how Black people fought to find belonging, and care for others, in a place riven with virulent violence and racism.

In the end, contributor Sylvia Roberts writes, it’s the complexity of the stories of the Golden Ghosts that will help counter “sanitizing history.”

That kind of history, Roberts writes, “deprives people of an opportunity to understand the struggles and achievements of Black people, and deprives Black people of the knowledge that their ancestors were an active contributing part of the nation’s history.”

You can purchase Voices of the Golden Ghosts here. Do you have a correction to this story? You can submit it here. Do you have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org