How an aging California is turning to senior centers for romance, community and health

No two senior centers are alike. We visited three very different venues in L.A. to learn how they’re changing for California’s aging population.

This story was originally published by CalMatters. You can sign up for their newsletter here.

Almeter Carroll sits alone on a couch inside the Watts Senior Citizen Community Center. It’s almost noon, but the place is nearly empty. Fitness mats and other workout gear lay stacked in a distant corner. No one shows up for a morning gym class except her.

She points across the room to a wall covered with photos of smiling, well-dressed Black men and women gathered at events throughout the years. “They’re all gone. Everyone on that wall. Passed away.”

It’s the same in her personal life. Widowed once, Almeter lost a second partner years later to COVID. For the most part, she likes being independent and taking care of herself. “Of course, I get lonely,” she says. “I miss my husband. I miss my boyfriend.”

She speaks of these things matter-of-factly, but still holds a positive outlook and carries a knowing smile. Quiet as it may be at the moment, the Watts center will begin to buzz with activity come lunchtime. Almeter will be surrounded by friends soon enough.

Older adults represent a significantly expanding portion of California’s population. By 2030, individuals over age 65 will begin to outnumber those under 18. But living longer also means people will see more loss, experience more grief and face more isolation.

Neighborhood senior centers may offer a good solution. They localize important resources and provide a safe, accessible space where older adults can go to find community and friendship.

“They’re absolutely essential and critical and part of the backbone of older adult services in our state,” said California Department of Aging Director Susan DeMarois. “They’re integral to our communities.”

Under Gov. Gavin Newsom, the aging department drew up a 10-year master plan that lays out five “bold” goals essential for sustaining longevity — housing, health care, inclusion, caregiving and affordability.

Senior centers can address the inclusion component, although how, exactly, remains unclear.

No two senior centers are alike. Local demographics and economic factors shape each center’s unique dynamics. With hardly any state oversight, most are largely left to themselves to figure out their own best practices.

In fact, no one can even say how many are operating in the state.

Former Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy sounded an alarm in naming loneliness and social isolation a national epidemic in a 2023 report — equating the long term health effects with smoking 15 cigarettes a day. One in five older Californians like Almeter live alone, making it even more difficult for them to maintain social connections.

Going to the senior center may benefit a person’s mental and physical health, according to a 2025 study by researchers from California State University Northridge and Kaiser Permanente. They distributed surveys at 23 Los Angeles-area senior centers to gauge how attendance affected the wellbeing of participants.

People who attended frequently — several times a week — or over long periods of time had better mental health and felt less lonely. Frequent senior center attendance was associated with greater reduction in loneliness among users under age 75, while the positive relationship between senior center attendance and physical health was more evident among users over age 75. Based on those findings, the authors encouraged local officials and doctors “to promote” senior centers as a healthy resource.

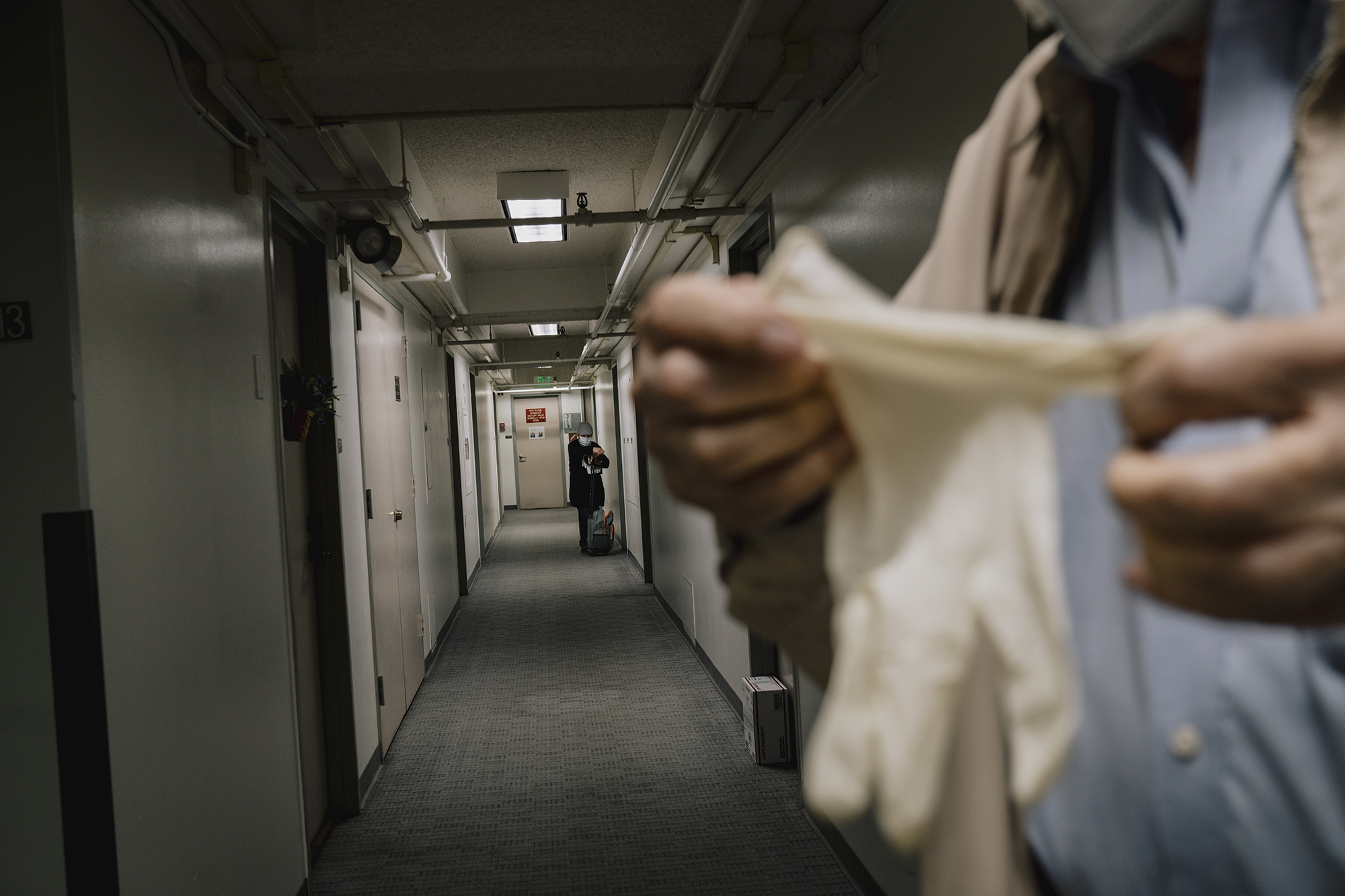

Hit hard by the social distancing impacts of COVID, community-based centers faced significant challenges when things began to return to normal. Older adults stayed away for some time out of caution.

But some returned to centers with a renewed focus on health and wellbeing. Rather than look for traditional recreation like bingo, post-COVID older adults wanted to see fitness classes and longevity training.

“As the population changes, as the opportunities change, as the needs change — senior centers evolve with that,” said Dianne Stone of the National Council on Aging. “At the core of it, senior centers are highly social places. It’s all about creating opportunities for social engagement.

“That might be just sitting around having a cup of coffee. It might be taking a class and finding people that are interested in the same things you’re interested in. But all of it is an opportunity to come in and meet people.”

Karaoke, tai chi and romance

Less than 20 miles from Watts, the Culver City Senior Center surges with energy and enthusiasm. Sunlight filters through large glass windows onto tables bustling with Mah Jong and other games. For $20 a year, participants get daily access to rooms filled with exercise classes, arts and crafts workshops and movie screenings.

Members gather early to hit the gym as soon as doors open at 9 a.m. Billiards players bring their own cues to shoot pool. Twice a week, packed-house karaoke sessions involve not just free-spirited singing, but also plenty of dancing.

On a sunny gorgeous day in mid-November, the karaoke team brought microphones and speakers out into the fresh air of Culver’s spacious central courtyard.

Selvee Provost bounced around and chatted knowingly with almost every person sitting under the verandas and shade umbrellas. As people took turns singing, she danced intermittently with different friends. Her simple social activity appeared to come naturally, but it was in the aftermath of loss and loneliness.

Selvee first came to the Culver center with her husband, Jim, in 2018. When COVID hit, things shut down. Then Jim died, and Selvee felt utterly alone. She could feel herself spiraling down in isolation.

“I knew if I sit at home and keep thinking about Jim, I’m gonna get more and more depressed,” she said. “That’s what motivated me to come here and try a class or something — just try anything.”

Tai chi became her pathway to community. “I didn’t know anybody, really. But by going to this class, I met people and learned they have a group about dealing with grief.”

That’s where she met Daniel Kerson. He’d lost his wife at almost the same time as Selvee lost Jim. “Both of us really needed to find companionship to survive,” she said. They moved in together right away and now come to the center throughout the week for classes, events and to socialize.

Louis Cangemi, a newcomer over the last few months, mingled with Selvee and made his own rounds amongst the outdoor karaoke singers and dancers. “I heard about this place and came to meet more people,” said the energetic 80-year-old. “I’m still a bachelor, so I hope to hit it off here with more women.”

But he might encounter a bit of competition. Other men like Jim Diego, 82, have been dancing and courting at Culver for years ahead of Cangemi.

A senior center shaped by its neighborhood

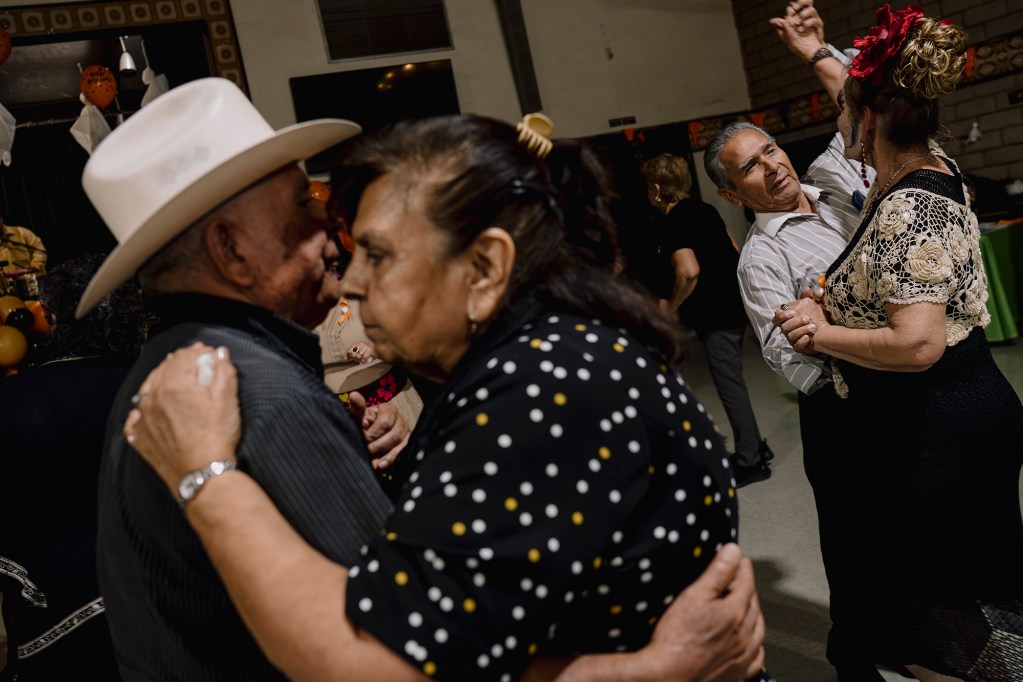

Coffee, tea and art — “Cafe, te y arte” — are the kind of social opportunities that begin each weekday at the Lincoln Heights Senior Citizen Center, all gratis for the mostly Spanish-speaking older adults who make themselves at home here. In one large community room, they share galletas and pasteles along with the free coffee.

As mid-morning hits, fitness classes like chair yoga and latin dance entice a dozen or so participants — predominantly women — to move, smile and laugh together beside the room’s raised performance stage. The men mostly sit and watch.

Twice a week, la lotería keeps the tables full for a couple of hours. Holiday dances draw crowds of over a hundred and feature DJs and live musicians.

“It’s such a lovely community,” said the Lincoln Heights director and one-man staff, Anthony Montiel. “I’m really fortunate to be part of this.”

As director, he maintains the schedule of classes and fills in wherever necessary. People are asked to contribute a few dollars per class, if they can afford it. In his backroom office, he logs in and accounts for handfuls of dog-eared $1 bills.

A lone ping pong player looks for the director in the afternoons. If he’s not too busy with his other duties, he’ll take a break for a quick match. “We have practically a brand new table,” said Montiel. “It’s nice equipment, but the guy usually has no one to play with but me.”

Shared meals, shared space, shared community

Putting a finger on the pulse of how senior centers maintain relevance, adapt and thrive is no easy task. Each center relies on a mix of different funding and resources.

Besides the classes and activities, subsidized lunch programs at all these centers play a crucial role in helping older adults stay healthy. The nutritionally balanced meals provide free or low cost sustenance, but offering the food in a shared, congregate space might be equally just as vital.

“When people are able to go to a setting like a senior center to enjoy a meal in the company of others, possibly to have music and entertainment and activities, that can be really good for people’s mental health,” said DeMarois of the Department of Aging. “That’s a big part of it — just trying to foster that connection and engagement on the preventive side.”

Congregate setting meal programs accounted for over 2.3 million older adult meals in the City of Los Angeles and in L.A. County in 2024, according to California Department of Aging records. But this data is not specific to senior centers, as it also includes meals in senior care facilities and other older adult group spaces.

“When it comes to senior centers, there is not good data,” said Stone. “There is not that central database of senior centers or community-based organizations, and there’s not even a shared definition of what they are.

“Senior centers are community responses to community aging. No two are the same because no two communities are the same.”

Speaking anecdotally from her own experience, Stone sees the bulk of most senior center populations as being between 75 and 85 years old. But that age range is evolving as older adult communities expand.

DeMarois sees the same dynamics taking shape. “When we talk about people 60-plus, we’re experiencing the greatest longevity ever right now,” she said. “The fastest growing demographic in California is 85-plus. We’re talking about four decades of life for many people from 60 to 100, so their needs and preferences will change over time.”

Back in Watts, Almeter’s not much interested in a free meal. “I eat my own food.” She sits around as other older adults filter into the center one by one. Many grab their subsidized lunch in styrofoam containers and soon walk right back out the door.

She waits patiently for her friends to arrive — women like Luretha Muckelroy, Maudell Robinson and Watts advisory board member Linda Cleveland. They gather here two or three times each week to play Spades or Bid Whist, card games that evoke plenty of smack talking and mirth.

“We need more men around here,” said Linda, as she notes the all-female crowd. Older adult males show up for some functions and events, but women seem to comprise most of the Watts center attendance.

For a few hours, the close-knit group makes the place come alive. Four players compete in two-person teams, while others keep tally. The losing team must vacate their seats.

They laugh, point fingers and chastise one another — all in good fun. The games can sometimes get heated. In between hands and shuffles, they share snacks and pour sodas.

When asked how she feels about aging alone, Almeter answers without hesitation. “Oh, I love being 87. It’s great to be alive.”

Joe Garcia is a California Local News fellow.

This story was produced jointly by CalMatters and CatchLight as part of our mental health initiative.

This article was originally published on CalMatters and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.