Opinion: My Life As A Criminal Sleeper

In this essay, Johnson reflects on the additional burdens the local justice system has inflicted on her already challenging circumstances. It’s only her strong support net, she argues, that keeps the system from unfairly labeling her as a criminal, driving her further into society’s margins.

Ed Note: This Opinion piece by unhoused community member Alissa Johnson is part of our new series, We the Homeless People, which provides first-person insight into the lived experiences of Shasta County’s unsheltered community members. You can read Johnson’s first story here.

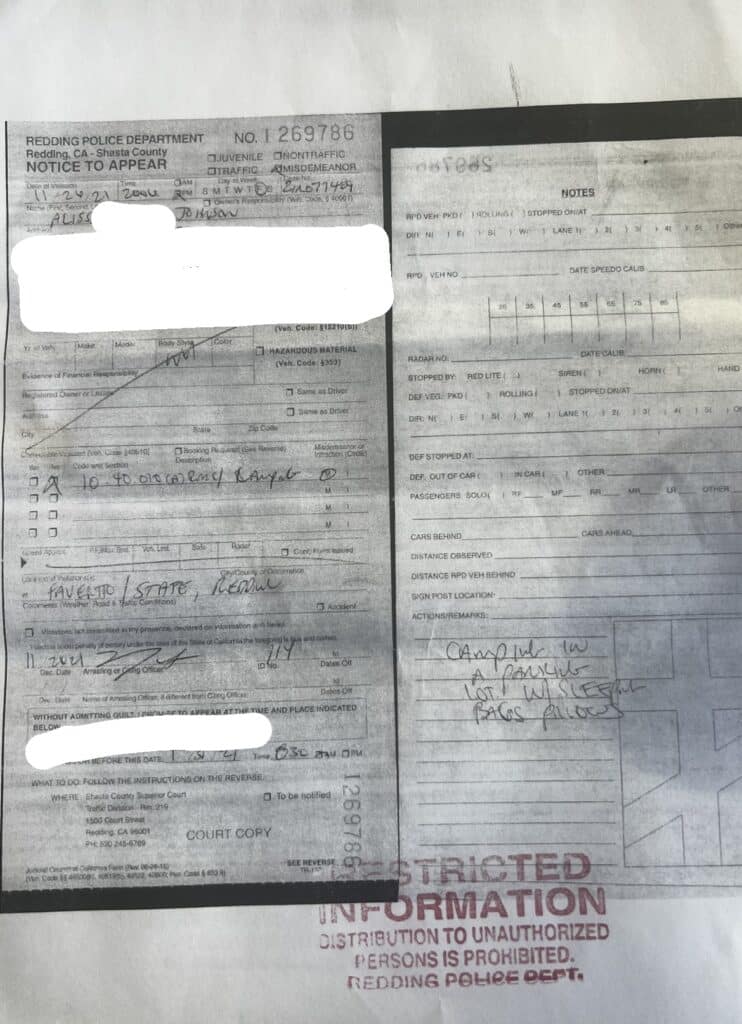

The citation happened so long ago I didn’t remember at first exactly where and when I had received it. But it must have been early in the morning when the Redding police officers cited me for that most horrendous of crimes: sleeping.

I had forgotten about the ticket that I got in late 2021 until a friend of mine, who has my name attached to their mailbox, received letters from the local court. That’s how I learned that I would have to go before a judge and defend myself for sleeping outside more than a year earlier.

I’ve received a few tickets in the past for sleeping outside, which were dismissed. But when I went to court for my most recent “illegal camping” ticket, I was told I have to participate in a program, or get in further trouble.

I have been unhoused in Redding since 2017, and I have dedicated myself to being an outdoor human. I am a professional cellist, and have been known in the past to do speed typing, as a volunteer for the Western Service Workers Association. But I haven’t found a place I can afford, and if I did I don’t have the skills to keep up the place which means I’d inevitably be evicted again. The last time I got evicted was when I lost my case manager years ago, and I know without support services, getting into a rental wouldn’t last.

For a long time, I was sleeping out in the elements, tarp under me and sleeping bag around me. I don’t always pitch a tent because I find that it is a “cop magnet.” I was usually sleeping outside near the South City Park fence or in the gravelly parking lot near the library at Favretto and State, which is where I got the illegal sleeping citation.

That’s the same lot where homeless community member Lori Rasmussen was killed last November by a semi-truck driver who ran over her tent while she slept. Shortly before she was run over, I had left my camp there to start sleeping in my pianist’s truck. I was tired of hooligans throwing fist-sized rocks at us and harassing us during the night.

Where are we, the unhoused people, supposed to sleep without the threat of violence, death or criminalization? We don’t have the right to sleep, much less the right to the pursuit of happiness.

In my eyes, the only crime I’ve committed is that I survived. My crime is I’m still alive . . . and they can see me.

I’ve seen people protesting “Stop giving (homeless people) rights!” We should have rights because we’re humans, regardless of what happens to us. But we, the homeless people, aren’t allowed to have rights. Instead we’re met with control.

The question becomes why would they try to control us like nuisance animals, instead of humanely helping us when we ask for it? The nuisance animal mentality is forced on us. By blocking us and harassing us from the places we sleep, they shoo us away like pigeons or treat us like runaway bears that you’re not supposed to feed.

The nuisance approach is counterproductive because our growth requires building trust and developing a support net.

How They Make Us Criminals

A while back, I got one of these sleeping tickets that came with a fine for hundreds of dollars, and I had to go to court to get them to reduce it. For some, paying a fine is an annoyance, but for me it’s a huge burden. Even though I’m homeless, I still have bills to pay. I sometimes pay up to $600 for food every month. My food costs are expensive because I have to always pick pre-prepared items or food that doesn’t need to be cooked.

My most recent citations didn’t come with a fine, but if I don’t keep going to court I could be arrested and labeled as a criminal. It’s outrageous that I risk having a criminal record for the first time in my life because I was fulfilling a basic human physiological need: sleeping. I say if I can’t afford rent anywhere, let me sleep.

Now, every three months, I have to go to court to prove that I’m participating in a Hill Country Community Clinic program. I call it diversion from poverty. I’m not on substances so they can’t send me to rehab. Instead the system pretends it can keep me from being poor, by letting me know about resources. But even with Hill County’s help, so far we haven’t been able to solve my housing problem.

People also don’t seem to understand how the whole process of going to court makes my struggle to survive even more challenging. I have to wake up in the frigid morning and walk in the cold and rain to make it to the court by 8 a.m. They must not know that keeping a successful schedule is a luxury, especially when you function around the movement of the sun, not by the hours on the clock. When it’s cold, it’s hard to get moving until the sun can touch us, and after dark, the frigid temperatures shut us back down into sleep. Technology like cell phones is hard for many homeless people to hold onto, destroyed by nature or stolen by other people.

What’s also difficult is when you’re not able to bring all of your belongings into the courthouse. They’re basically demanding that many of the unhoused people who are outside leave their stuff out in the open with nobody to watch it, vulnerable to theft.

I still don’t even know how long they’ll make me continue to do my days in court. It’s undecided, there’s no timeline or endpoint. I just get instructions to show up again in another 90 days. I assume this means they’ll do this until Hill Country can help me prove I’m what they deem a ‘productive’ person. But if the police and courts got to know me, they’d know I already am a productive person, a professional musician who performs at regular gigs and a writer who contributes to the community.

I don’t have a car, I don’t have a house to clean up or warm up. I am thankful I do have my sister who keeps me on her phone plan, and I pay my share of it monthly. Shaw Campbell, my worker at Hill Country, is a cool dude. He understands why I feel this process is unhelpful, and he works with me to keep up on court appearances. I’m lucky for the people that hold my world together to get me to these places, otherwise I’d be a sitting duck: I would miss court appearances and the system would turn me into the criminal they want me to be.

Once I’m a criminal, it would validate all of their abuses against me. Nobody gives a damn about you if they manage to plaster the word criminal over your life.

It feels like this system is built to pump homeless people into the prison pipeline. This is what happens when homeless people who are in the thick of it don’t have a voice at the decision-making tables. Without representation from the marginalized community guiding the way, even well-intended aid can become traumatizing.

Gimme Micro-Shelter

My hopes rise as the applications for the micro shelters opened up for circulation on the 15th. It’s been a long effort, and it is fulfilling to see real solutions becoming reality. The micro-shelters are transitional housing units that have a bed, heater as well as access to a bathroom and kitchen.

The community partners organizing the micro-shelter people have involved us along the way to help build the supportive structure we’ll need to thrive there and eventually in permanent housing. They are focused on building trusting relationships with us and amplifying our voices. They’re doing it for us and with us, not to control us.

Currently, there are only eight micro-shelter beds, but I’m hoping that more locations will be opening up. I’m focused on making sure the micro-shelters are a successful endeavor. Many of us have had our tents or makeshift shelters destroyed by the snow. Then after the snow wiped us out, our belongings were drenched by the rain. Personally, I am looking forward to hard walls.

Shelter, trust and collaboration are what we need. Not sweeps. Not harassment. Not citations. And not the system’s “homeless parole” that tries to turn us into criminals for simply trying to survive.

Do you have questions, comments, or feedback on this Opinion piece? Email us: editor@shastascout.org