Safety versus surveillance: Shasta considers implementing automatic license plate readers

Local law enforcement says license plate readers play a significant role in investigations. Reporting has shown there’s little oversight to prevent local police officers from misusing the technology.

From up to 75 feet away, even in darkness, Redding’s automated license plate readers (ALPR) can scan a car’s license plate in a flash. The number is then compared against different “hot lists,” — or catalogs of vehicles of interest to law enforcement — which can include stolen cars, vehicles associated with Amber Alerts, or those connected to open investigations. Depending on what vehicle is being driven, simply passing through particular intersections may prompt a notification to the Redding Police Department logging your presence.

That’s a positive, RPD Chief Brian Barner says, calling the plate data “ a valuable tool for our investigations” that can be “ instrumental” in solving cases.

RPD’s use of ALPR technology is colossal in scope; according to LPR data obtained by Shasta Scout. In 2025 alone, RPD’s cameras scanned license plates more than 43 million times within the city limits of Redding. Of those, 65,000 hits registered a vehicle of interest, either to RPD or one of the affiliate departments with which RPD shares so-called hot lists.

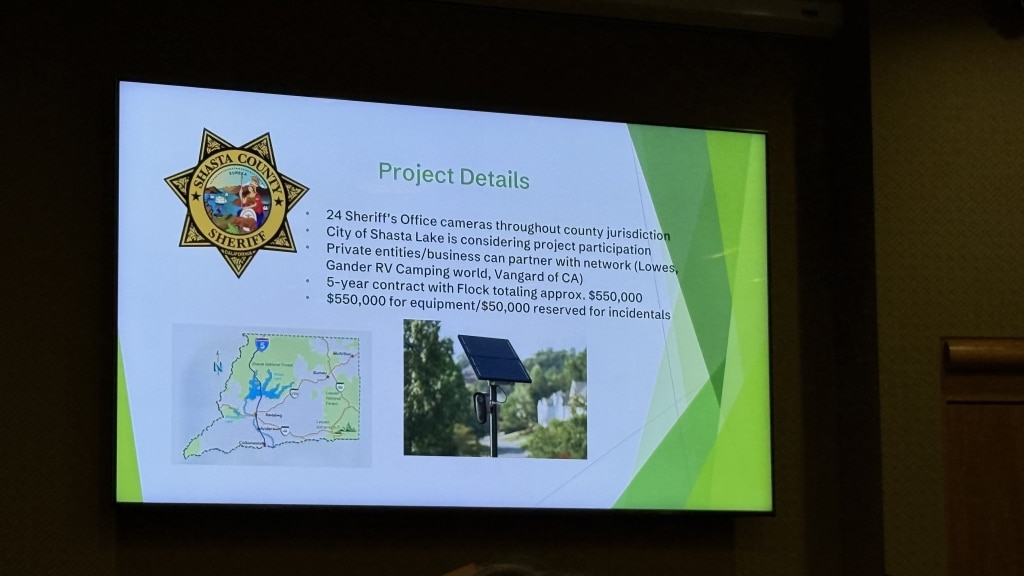

This week the Shasta County Sheriff also hopes to get approval to invest in ALPRs which would be installed in parts of the county outside of Redding’s city limits. At a community listening meeting about the plan, held by the Sheriff on Oct. 29, local residents brought up a number of worries about privacy. They cited cities like Hillsborough, North Carolina, where police have canceled their ALPR contracts due to “concerns about data security.”

In tandem with many communities around the country, the listening conversation held last week revolved around the tension between people’s expectation to protect their own personal information and the idea that relinquishing their data could make them safer.

In response, Sheriff Michael Johnson acknowledged to those who attended the meeting that he shares some of those same fears about technology, adding that he stays off social media “because I don’t trust what’s being gathered of my information.” But, he said, he feels trustful of Flock Safety, the ALPR vendor the county has their eye on, adding, “I think it’s the best system out there, and we’re willing to give it a shot.”

This Thursday county supervisors will consider investing half a million dollars in 24 Flock ALPRs to monitor ingress and egress points at county limits. The contract, if approved, will last five years.

It’s important to note that while investing in ALPRs can help solve crimes within a particular jurisdiction — such as Redding or Shasta County — the data collected doesn’t necessarily stay local. Once scanned, the technology can be used to share license plate numbers with other police departments all over the country, and in certain cases, even with federal agencies such as ICE.

Though California police officers are legally prohibited from sharing data directly with immigration enforcement, past records requests and investigations have shown that ICE has accessed local California data to track vehicles and conduct arrests. In some recent cases, officers in Southern California also conducted license plate searches on behalf of Border Patrol and Homeland Security — a breach of that law.

How does local law enforcement use ALPRs?

In the summer of 2020, the city of Redding entered an $800,000 contract with the ALPR manufacturer Vigilant Solutions (a subsidiary of Motorola Solutions). That purchase included some 42 cameras, hardware, and access to the centralized database the department uses to share their hot lists with public agencies and police departments across the country. Other agencies operating within Shasta County also use ALPRs including the Anderson Police Department, California Highway Patrol, and even the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

To give an idea for how this technology can aid the police, RPD’s license plate data was utilized by investigators in some of the county’s highest profile cases in recent months – the disappearance of Nikki Saelee-McCain as well as an investigation that led up to confrontation where a Redding Police Officer shot David Schaeffer.

While the exact locations of the cameras within the city are currently shielded from disclosure by RPD, the public can request the audit logs that track when and for what purpose police officers search databases of license plate numbers. An audit conducted by the advocacy group Oakland Privacy in June discovered multiple cases in which local police officers in California were looking up license plates in searches that referencing Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) or Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). Also of note, many searches audited by Oakland Privacy found law enforcement officers listing only vague criteria such as “investigation” or the pound sign making the true motive of the search impossible to determine.

In line with the California Values Act, as well as RPD and county policy, both Chief Barner and Sheriff Johnson confirmed that neither agency engages in immigration enforcement, including in the process of how they use, or intend to use, ALPR data.

Additionally, at the Sheriff’s community meeting, Lieutenant Bodner confirmed that once his team has installed their ALPRs, the policy will require officers to clearly notate the purpose of their license plate searches for public transparency.

Asked if RPD has a similar policy requiring officers to clearly document the reason for the use of ALPR data, Chief Barner relayed instead that officers have “a department policy that covers all our technology systems … a need to know, right to know” for access to any information. Anyone accessing has to have a work related reason for accessing information – such as an investigation, call for service, etc.”

RPD’s memorandum of understanding, which outlines how the department should be sharing data with other agencies, requires that “each transaction is to be logged, to include a case number, and an audit trail created.” Barner’s response did not directly address the question of whether specifics of why ALPR data was accessed must be written into those logs. Shasta Scout has submitted a PRA for RPD’s ALPR audit logs over the past year and is still pending a result.

California’s sanctuary laws are not the only policies that limit how ALPR data is used. Senate Bill 34 also prevents local police officers from sharing license numbers with other out of state agencies. But a Calmatters investigation found that police departments up and down the state also routinely violate this law. This prompted Attorney General Rob Bonta to issue a bulletin with further guidance in 2023, emphasizing that this data should not be breaching California’s borders. In the case of some agencies, this was to no avail.

Amid this lack of compliance, Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill on Oct. 1 that would have both required officers to identify the purposes of their searches and implemented a policy requiring the DOJ to conduct random audits of ALPR use.

Motorola Solutions’s main competitor Flock Safety (which the Shasta County Sheriff plans to contract with) has publicly-accessible “transparency portals” integrated into their systems showing all the agencies each individual vendor shares data with. Data from the system shows that the city of El Cajon continues to coordinate with law enforcement in other states. The city is being sued by the Attorney General for its refusal to comply with California’s regulations.

As for RPD, a records request last month showed that as of 2025, the department is complying with SB 34 by not sharing its data with any agencies outside the state. That’s in stark difference to a similar records request issued to RPD in 2022, which revealed the department was sharing detection data with local police in New Jersey, Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Nebraska as well as with Customs and Border Patrol. As allowed under California law, RPD continues to receive ALPR data from outside the state – including from places as far away as New England. California law prohibits the sharing of local data with out-of-state public agencies, but not the other way around.

The capability for officers to exploit ALPR technology toward illegal ends – such as coordinating with ICE from a sanctuary state, or in rare cases, stalking an ex-partner – is part of the reason why watchdog organizations like the Chicago–based Lucy Parsons Lab have produced educational resources to help the public understand the historical development of surveillance tools and their use by law enforcement. One of the labs’ researchers, Ed Vogel, who successfully sued the Atlanta Police Foundation over their withholding of public records in June, spoke with Shasta Scout about why he’s opposed to empowering law enforcement with Flock and Motorola’s massive ALPR infrastructure.

Vogel described how sudden change to data protection law could open the door for law enforcement to utilize these kinds of tools of surveillance toward new and unexpected targets and in some cases criminalize certain people’s movements.

The watchdog researcher cited abortion access as an example saying states like California, Illinois, or New York “probably did not anticipate that ALPRs would eventually be used for abortion monitoring – but then the Roe decision came down.”

As just one example, in May, a 404 Media investigation revealed how a police officer in Texas searched data from 83,000 ALPRs including those from states as far as Illinois and Washington — where abortion is legal — as part of an investigation into a Texas woman suspected of terminating her pregnancy.

This story is part of “Aquí Estamos/Here We Stand,” a collaborative reporting project of American Community Media and community news outlets statewide.

Do you have information or a correction to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org.

Comments (1)

Comments are closed.

With our super high car thefts in Redding/Shasta County, this seems like a really important tool to catch the thieves, now if we get the jail capacity back and the courthouse dried out, maybe put some of the frequent fliers in prison.