“My ancestors have not deserted me”: The life and writings of Wintu poet Alfred Gillis

After recent erasures of the historical contributions and experiences of Indigenous people from public sites, the work of an early 20th century Wintu poet provides poignant insights into how local Native people have fought against invisibility for centuries.

On April 19, 1922, Alfred Gillis, a tailor and poet from Shasta County, stepped before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Indian Affairs in Washington D.C. to testify on behalf of his Winnemem Wintu relatives and California Indians from throughout the state.

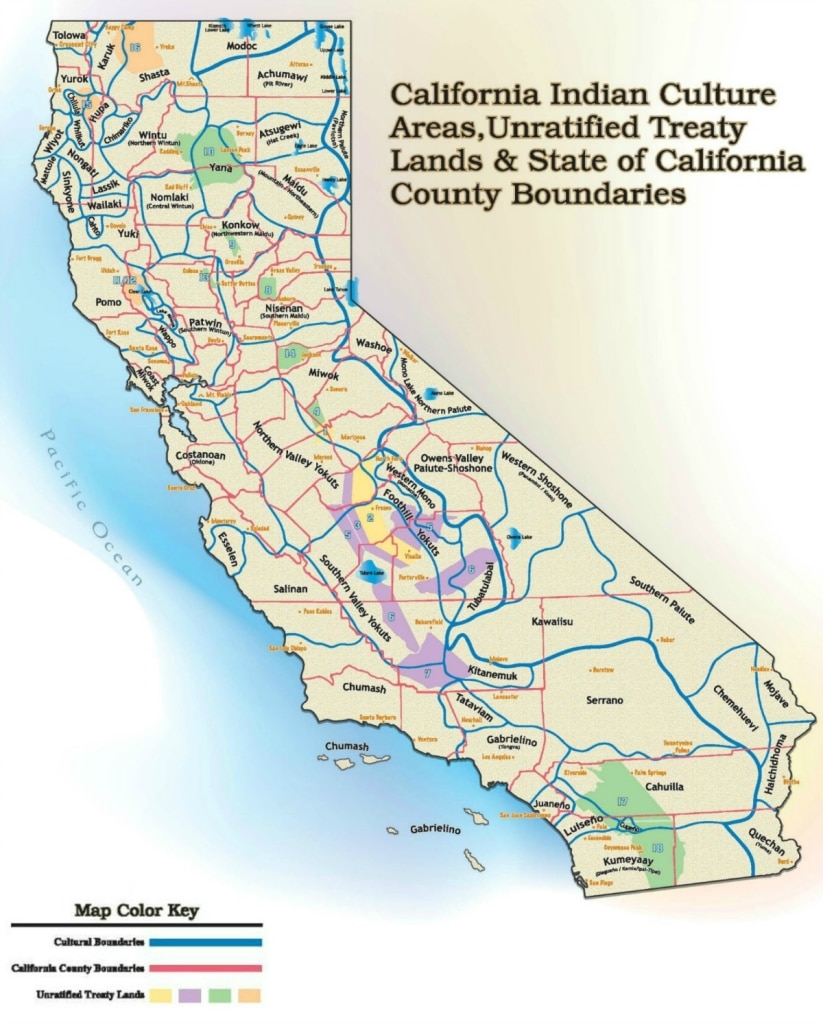

The hearing was focused on a bill that would authorize thousands of Native people in California to file a lawsuit against the federal government demanding compensation for their stolen ancestral lands. About 70 years prior, the U.S. Senate had refused to ratify 18 treaties and opened the floodgates for Euro-American settlers to illegally seize Indigenous lands. Now Gillis and other Native activists were demanding justice in the halls of power.

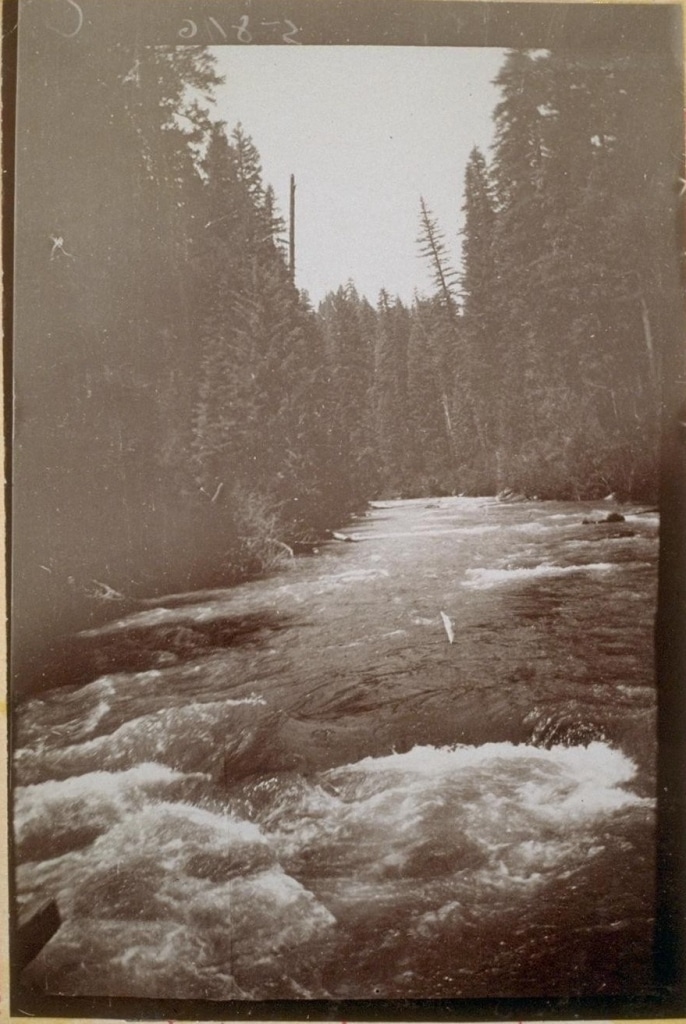

Speaking to representatives that day, Gillis demonstrated both his poetic skills and his mastery of the Tribe’s oral history. In 1851, he explained, government agents came to the McCloud River — the Winnemem Wintu’s homeland — offering gifts to tribal leaders and requesting that they “put down their bows” to sign a treaty with the United States.

Negotiated at Pierson B. Reading’s Ranch the Cottonwood treaty provided Wintu and Yana people a 30 mile square reservation which included land on the west side of what is now Redding — and protection from genocidal Euro-American settlers. In exchange, the Wintu and Yana relinquished the aboriginal title to their vast homelands.

However, the Senate betrayed the Wintu and Yana people, as Gillis explained to the representatives, refusing to ratify the treaty or create the reservation. Many Native people, who had already begun migrating to the reservation, became homeless as the government allowed settlers to seize the land.

To emphasize the prolonged feelings of betrayal this engendered among his people, Gillis shared a story about a chief who was buried on the McCloud River with a copy of the treaty he signed as a symbol of the Tribe’s long deferred calls for justice.

Perhaps unsure of the veracity of Gillis’ account that day, Representative Carl Hayden from Arizona responded to his historical recitation by questioning the poet about the nature of his racial heritage. Gillis revealed he was a quarter Wintu, explaining that while his White father had abandoned his family, the Wintu people took care of him.

“My Indian ancestors have never deserted me,” Gillis proclaimed.

A Wintu Poet’s Intergenerational Call for Justice

The century-old exchange provides a revealing testament to Gillis’ steadfast pursuit of justice, which was rooted in an unwavering commitment to Winnemem Wintu knowledge and traditions.

Despite the ravages of genocide, displacement and government duplicity, the poet refused to give in to the forces of assimilation and worked to organize California Indians around the state to join together in their land claims. Simultaneously, he fought for a better future for Tribal people by advocating against the systemic discrimination that had long restricted Native peoples’ access to public education and health care among other civil rights as U.S. citizens.

At a time when President Donald Trump’s executive orders have led to the removal of Indigenous history from federal sites such as Muir Woods National Park, Gillis’ work is an instructive reminder of how Indigenous peoples have successfully resisted previous campaigns of erasure and invisibility, even when it required activism across multiple generations.

Gillis used his writing and speeches to advocate for the beauty and sophistication of Winnemem Wintu and other California Indian societies despite the federal government’s assimilation policies during that era. For some contemporary Wintu, Gillis words echo across time expressing a world view and connection to homelands that reminds them of their own.

Poems Rooted In Wintu Philosophy and Place

One Gillis poem, “The Bird with the Wounded Wing”, tells the story of a Wintu man rescuing an injured bird from a snowy death by placing him in his warm black hair. He then mends the wing and the bird flies away, healthy and free. Years pass and the man is on his deathbed, “helpless and alone”, when the bird miraculously returns and sings a song to comfort him.

He sang away the Indian’s pain,

Alfred Gillis

And brought new life and health again.

This is the tale the Shaman told.

This is the tale the mountain told.

This treasure in these words I find,

The greatest good is to be kind.

“(The poem) is a reminder to live in a good way, to be a good human, to think about how everything is reciprocal and interrelated,” Kenwa Kravitz (Wintu/Madesi Pit River) said in response. “When I read the poem, I think these are things we’re taught that should encompass every action and relationship. We can’t forget them. The ability to share that Wintu way of thinking and being is a gift for us and for all human beings.”

In another poem, “To the Wenem Mame River,” Gillis uses the Winnemem name for the McCloud River. It’s a reminder to both settlers and his people of the original language of the watershed. The poem also references the renowned Winnemem Wintu leader Norel Putus, and evokes a rich history of the Tribe’s stewardship and occupancy of the watershed which far predates the river’s “discovery” and renaming by the Hudson Bay Company.

Of all fair rivers I have known,

Alfred Gillis

No fairer waters than thine own.

O, topy mame, we love thy name

Famous waters Wenem Mame.

Here Indian youth and maiden strayed

And nature’s children laughing played

And near you tall piney wood,

Once the War Chief’s village stood.

Where chants from a thousand throats

Rose unto Heaven in sweetest notes,

Here Norail-poot-as lived and died

And now lies sleeping by thy tide.

For contemporary Winnemem Wintu Tribal member Cassandra Curl, Gillis’ poems resonate because his incorporation of Winnemem Wintu place names, plant knowledge and values communicate a kinship with his ancestral watershed that feels familiar to her own.

“It’s so important for Indigenous people to connect with our homelands and to recognize the beauty in the ancestors that were there before us,” Curl explained. “When I read his poems, I can just imagine him sitting by the river, watching the things he observed, and feeling that connection.”

From Indian boarding school survivor to political activist

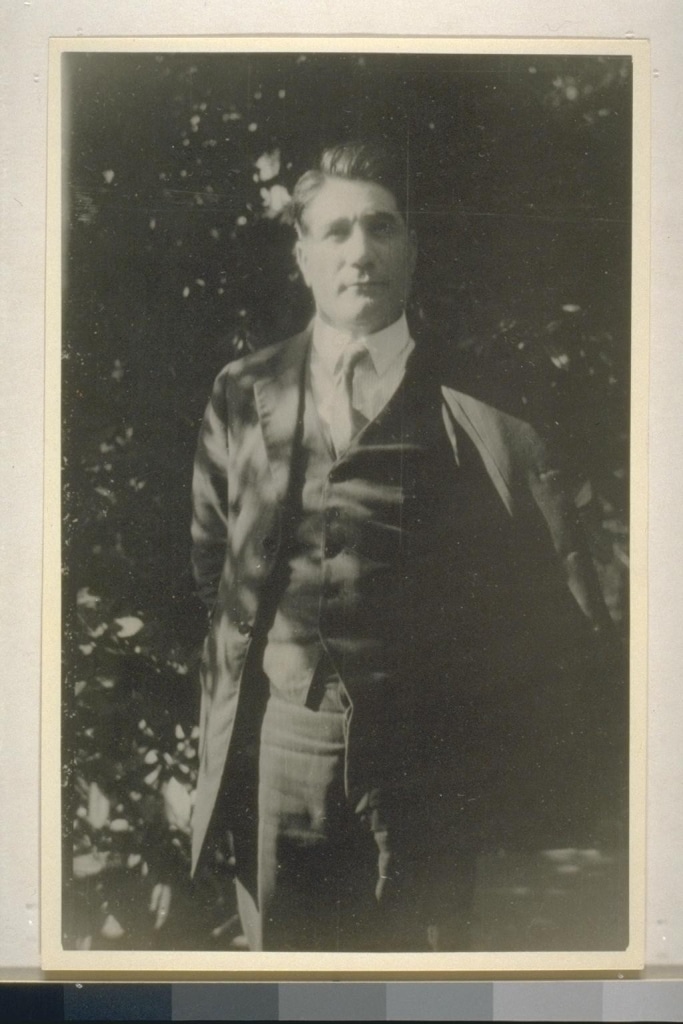

Gillis likely learned to read and write when he was separated from his family and sent to the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon from ages 9 to 19. It may have also been at Chemawa where Gillis learned his trade as a tailor — in the remaining photos of Gillis, he always appears in a neat and dandified suit.

Chemawa was one of more than 350 government-sanctioned boarding schools that officials built and operated with the intent of stripping Native children of their cultures and assimilating them into White, Christian society as manual laborers and homemakers. While the boarding schools had devastating impacts on Indigenous families and Tribes, Gillis used the education that was meant to erase his Winnemem Wintu identity to fight for his people’s land claims and civil rights.

In the 1920s, Gillis became an important figure in the inter-tribal movement to lobby the U.S. government to compensate tribes in California for the unratified treaties. The Wintu and Yana peoples’ treaty was one of 18 treaties signed up and down the state by hundreds of Tribal leaders between 1851 and 1852. Had the treaties been honored, they would have established nearly seven-and-a-half million acres in reservations, encompassing about 1/12th of California’s land.

The treaties were sent to the Senate — which under the constitution had the responsibility, along with the President, to evaluate and decide whether to ratify them. As documented by several historians, the Senate rejected the 18 treaties and hid them away from public view for 55 years under a secret injunction. The documents were recovered in 1905 by white progressives who were raising awareness about the destitute conditions of Native peoples in California.

As public outrage about the lost treaties grew in the early 1900s, Native communities created auxiliaries around the state to organize community events, raise funds and send delegations to Washington D.C. to lobby for their land claims. Gillis was the first chairman for the Baird Council Auxiliary, which consisted mostly of Winnemem Wintu. He also traveled around the state, visiting other tribal communities to build support.

During this fertile time for inter-tribal activism, Gillis published his poems, travelogues and essays in the California Indian Herald, a periodical that ran for only a year in the 1920’s and featured many Native writers who were involved in the land claims movement.

According to Caleen Sisk, Hereditary Chief of the Winnemem Wintu Chief, Gillis was uniquely talented as a political advocate, having a strong foundation in his tribal culture and the ability to communicate to mainstream audiences. “Alfred knew his traditions and he also knew the White man. That’s why he was such a good speaker in D.C.,” Chief Sisk told a reporter when asked about Gillis’ approach.

In many of his essays, Gillis sought to combat the pernicious stereotypes that California Native people — sometimes derided as “diggers” by Euro-American society — were primitive, dim-witted and barely human. At a time when even benevolent Whites thought Native people should assimilate to survive, Gillis wrote eloquently about the beauty and sophistication of Indigenous ways of life, confronting the racism he saw as barriers to justice.

In a 1923 essay titled the “The California Indians,” Gillis extolled the talents of Wintu basket weavers as well as the awe-inspiring beauty of the Big Head dances while comparing the Tribe’s oral tradition to the best work of Western historians. He noted that he learned from Elders steeped in their oral tradition whom he described as “historians among the Indians.” He noted they gathered in council houses to “sift” through their stories and “gather facts and pass them down to their children.”

By 1928, the advocacy of Gillis and other Native people appeared to score a major victory when Congress passed a bill that authorized the state attorney general to sue the United States over the 18 unratified treaties on behalf of the Tribes. But the case wasn’t resolved by the Court of Claims until 1944 — and payment wouldn’t come for more than another decade.

Planting Seeds for Future Justice

In April 1947, as California Indians continued to wait for checks to reimburse them for their stolen land, Alfred Gillis again testified before the House Committee on Indian Affairs.

Since his presentation to Congress in 1922, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had erected the 602-foot Shasta Dam, flooding more than 27-miles of his beloved McCloud River and displacing an estimated 400 Winnemem Wintu. With his people in a full-fledged diaspora, Gillis struck a far more somber tone, speaking of young Wintu who were drifting away from their ceremonies and telling stories of McCloud River chiefs putting aside their bows and war bonnets in resignation.

Yet Gillis still used the opportunity to advocate for payouts from the claims case to be distributed and for Native people to have access to their full rights as U.S. citizens. In 1954 — decades after their land was taken — 33,000 California Indians finally received paychecks for their stolen land, although only a mere $150 dollars each.

With such paltry payouts, Gillis never saw full justice for the unratified treaties, but his writing and activism as well as the resilience of other Wintu ancestors planted seeds for future victories. Cherokee literary scholar Daniel Heath Justice notes that like Gillis, many Indigenous writers use their voices to speak justice to future generations, providing guidance for their descendants to carry on a fight that outlasts individual lifetimes.

In this fashion, Gillis’ writing and words have inspired generations of Wintu who now live at a time of revitalization that Gillis might never have imagined after construction of the Shasta Dam. In recent years thousands of acres of land have been restored to Winnemem Wintu stewardship and salmon have returned to the McCloud river for the first time in 80 years.

“Gillis took a tool of erasure (the English language), and used it to create beauty,” Kravitz said. “He is an example of our ability to continue on as Wintu people and adapt and carry that goodness in our heart.”

Do you have information or a correction to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org.