Redding Police Clear Long-Term Homeless Camp Off Masonic Avenue

About seventy people used to live on private land off Masonic Avenue. After new gates were placed around the property in March, some moved on. Those who remained, about forty, have been displaced by police enforcement over the last two weeks.

Eric Hiatt is renovating a series of apartment units that line the end of Masonic Avenue. He owns the apartments under the business name Downtown Collection LLC.

Hiatt, who is also a member of the Shasta Angels, says he’s grateful that the City is finally cleaning up the property next door to his, which has housed one of Redding’s largest homeless camps for several years.

On Wednesday, May 24, Hiatt was on site at the Masonic camp to thank Redding police, who had just finished arresting the last three unhoused community members who still remained on the property.

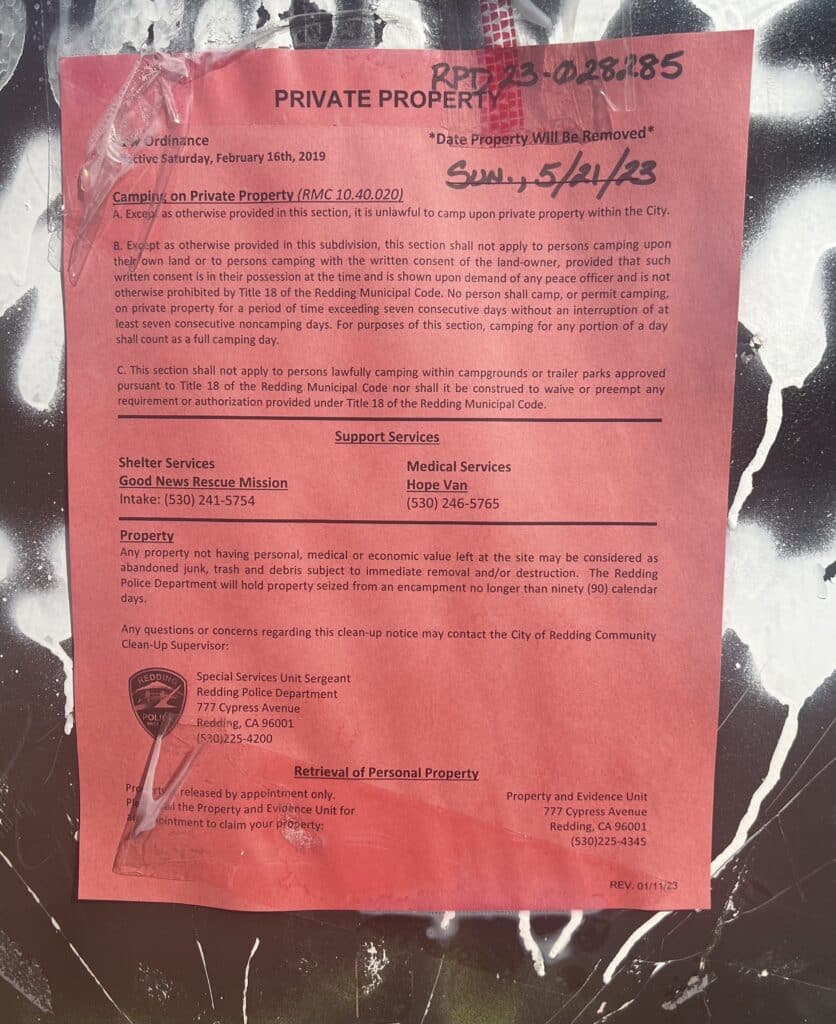

The arrests were part of the City’s enforcement of anti-trespassing laws with the permission, they say, of the property’s owner, Allen Ansari, who holds the parcel under the business name Sundial Villas LLC.

Redding Police Officer Jon Sheldon told Shasta Scout the City has been levying code enforcement fines of $1000/day on Ansari to incentivize him to agree to the cleanup efforts.

A January decision about Ansari’s property by the City’s Board of Administrative Review helped begin the enforcement process, months ago.

“He’s a good guy,” Hiatt said of Ansari, whose address is listed as Morgan Hill, California. “He just kind of gave up on the problem.”

Hiatt says he’s spent months helping push the City to clear the camp which has an effect on the value of his nearby rental units.

He’s also the one, he told Shasta Scout, who paid to install new twelve-foot wrought-iron fencing at the site in February, significantly limiting access.

Over the last few months, during repeated visits to the Masonic camp, Shasta Scout has interviewed a number of the community members living there, in efforts to learn about the barriers they experience to housing and other services.

Until recently, the Masonic encampment housed about seventy community members who lived in approximately eighteen different sub-camps. There was significant substance use and some violence at the site, according to Shasta Scout’s interviews, but also a neighborly spirit among many of the residents, some of whom had built significant home structures over time.

While many individuals at the Camp were largely independent and self-sufficient, they also worked cooperatively to help others, especially the older residents at the camp, including one woman in her seventies who was largely unable to leave the campground because of significant mobility issues.

Some community members described a social structure at the camp that included authority figures sometimes known as the “shot callers” whose permission was required for actions by other campers that could affect the rest of the site, including calling for emergency help.

Masonic camp residents carried water from nearby taps and charged their phones using outlets at nearby buildings when given access by sympathetic employees or property owners. In the winter snow and cold, they kept warm with small propane cook stoves inside their tents and small fires under their tarps.

Those warming and cooking fires have led to several wildfires in the Masonic camp site over recent years, at least one of which threatened nearby homes.

When Hiatt installed the metal gates in February, some community members at the camp moved on, driven by fears that the gates could trap them on the property, without an easy way to leave if police or vigilantes showed up.

About forty people were still living at the Masonic camp a few weeks ago, Officer Sheldon said, when police enforcement began.

That enforcement came, City Manager Barry Tippin said, only after many months of “outreach” by the Redding Police’s Department’s Crisis Intervention Team (CIRT), which includes two RPD officers and a County mental health worker.

The City launched its first CIRT team in 2021 as a way to offer resources to those living outside, in attempts to connect them with needed services, including shelter.

But many living at the Masonic Camp have not taken CIRT’s offers of shelter because existing local options aren’t a good fit for their needs.

Those options include the faith-based Good News Rescue Mission and a partially City-funded private nonprofit known as No Boundaries, which offers temporary hotel stays of up to ten months. Both programs have restrictive rules and requirements, which limit access for many in the unhoused community.

During interviews with Shasta Scout over recent months, some Masonic residents said they were unable to shelter at the Mission and No Boundaries because they wanted to maintain access to their pets or possessions.

Others said they had already been banned from the Good News Rescue Mission over past violations of the shelter’s rules.

Some unhoused people also said they worried about how No Boundaries’ restrictive rules would limit their ability to leave the transitional housing site to visit friends, work, or move around during the day.

They were describing what is known in housing lingo as barriers, including limits on access to pets, possessions, substance use, and movement. Those kinds of rules are no longer allowed in State-funded programs, because evidence-based research has shown that they reduce the chances that unhoused community members will access housing and maintain it long-term.

Instead, California now requires what is known as a “Housing First” approach to shelter. By focusing on providing emergency or transitional housing first, service providers can provide the stability and security many in the unsheltered community will need to receive further critical help, including mental health treatment and substance use services.

Shasta County does not yet offer any Housing First emergency or transitional shelter space, limiting options for many who are living in camps like Masonic.

Police told Shasta Scout that approximately twenty of the forty people still living at the site two weeks ago have accepted offers of temporary shelter, mostly at the Good News Rescue Mission or No Boundaries.

It’s not clear how many of those individuals were accepted into one of those shelter sites or whether they continue to maintain shelter there now, a few days or weeks later, after encountering restrictive rules.

A few months ago City staff said they were not tracking how many of those referred by CIRT to the No Boundaries program were maintaining shelter there or for what reasons they were choosing to leave the program.

If you have a correction to this story you can submit it here. Have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org

Through December 31, NewsMatch is matching donations dollar-for-dollar up to $18,000, giving us the chance to double that amount for local journalism in Shasta County. Don't wait — the time to give is now!

Support Scout, and multiply your gift