California hospitals brace for impacts from ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Medicaid cuts

The “One Big Beautiful Bill” cut billions in Medicaid funding. Those working in health care predict these cuts will severely impact hospitals that serve largely low-income populations, including rural hospitals like those in Shasta County.

In 2023, the only general hospital in Madera County closed due to financial distress. The Central Valley health care center mostly served low-income patients and relied on government-funded programs like Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, to partially fund that care.

That’s problematic because government programs like Medicaid often pay providers below the cost of care, making it difficult for hospitals that serve a high number of Medicaid patients to continue providing all services and to even keep their doors open. The closure of the Madera Community Hospital, which has since reopened, caused a domino effect: clinics affiliated with the hospital closed, so people needing care tried going to a nearby children’s hospital, which was only designed to treat children with its smaller beds and equipment, or to hospitals in Fresno, which started seeing more patients in emergency rooms.

With recent federal cuts to Medicaid, health care officials in California are worried more hospitals could face the same fate.

“We don’t want to see that situation repeat itself again, if we can help it at all,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, spokesperson for the California Hospital Association (CHA). “We’re very concerned because of the impact.”

The federal budget reconciliation bill, also known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” was signed in July and includes significant cuts to Medicaid. Experts say these cuts will not only impact those who lose Medicaid coverage, but may also severely affect hospitals that serve a large proportion of low-income people, something that’s more common in rural areas.

They explained it like this: The millions of people who could lose coverage due to cuts will still need medical care. Since hospitals are legally obligated to provide care to people regardless of insurance coverage, they will treat those uninsured people — but won’t get paid for it. The resulting revenue loss may lead hospitals to reduce overall services to make up for the lost costs, or in dire situations, close entirely if they can no longer support the facility’s operations or staff.

Peggy Wheeler is the vice president of rural health care and governance at the CHA, a non-profit that provides advocacy and representation for the majority of California hospitals at state and federal levels. Like her colleague Emerson-Shea, she’s concerned about the impacts of Medicaid cuts on hospitals throughout the state, especially rural ones, like those in Shasta.

“This is not a short-term problem,” she said. “This is a really long-term problem, and it’s going to take long-term thinking, long-term and innovative approaches to how we are going to adjust to the new health care system. I think that our hospitals have weathered a lot of storms, but this one feels a bit different.”

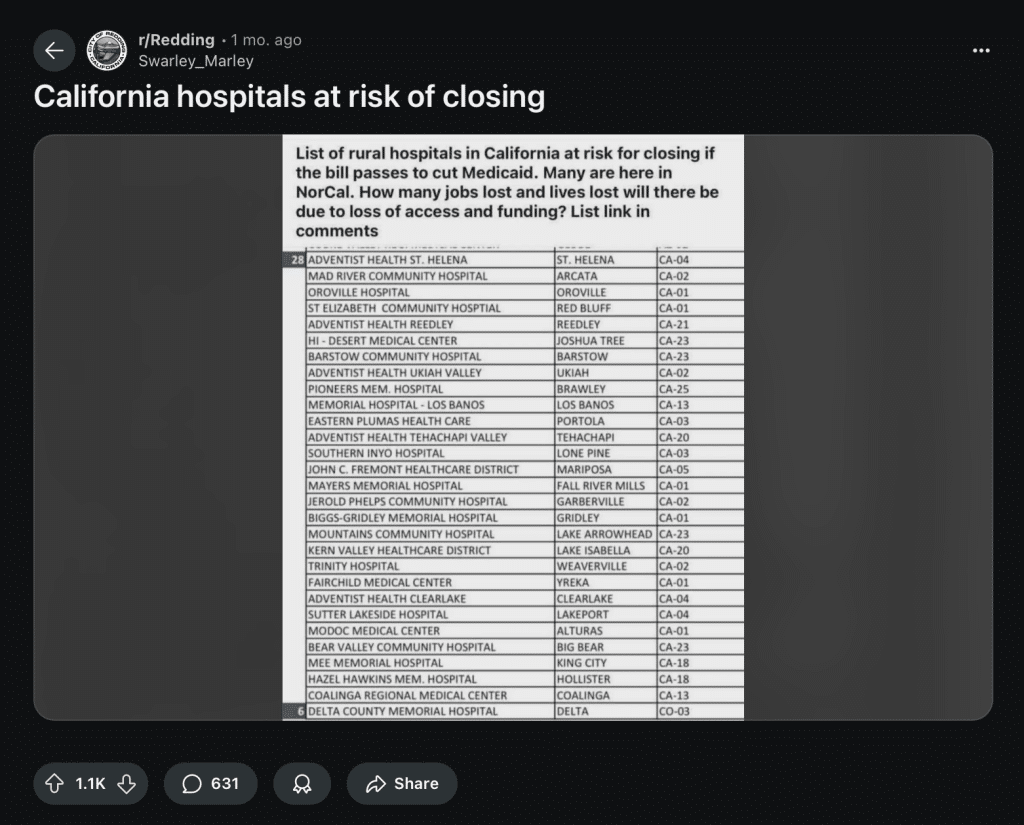

A few weeks before the bill was passed, a letter from several U.S. senators to President Donald Trump and other government officials about the risks of Medicaid cuts to rural hospitals was widely circulated online. The letter names more than 300 hospitals nationwide at risk of closing or having to reduce services due to cuts, including Mayers Memorial Hospital in Shasta County and several others in the North State. It was based on research provided by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina.

CHA officials said this list isn’t entirely accurate because of how the hospitals were calculated to be at risk, noting that several hospitals they believe to be at risk weren’t included. Wheeler explained that the researchers only looked into two characteristics, one about how many years a hospital has been in negative margins and another about how many Medicaid patients they see, when other factors should’ve also been considered to make final calculations.

Nonetheless, she said the point of the letter was still an important one to make.

“In general, what the senators did was call attention to an issue that is real,” Wheeler said. “The One Big, not-so Beautiful Bill is going to be problematic for these hospitals that, for the most part, operate around the margins providing care, not getting appropriately reimbursed for the cost of care.”

Shasta Scout reached out for comment to five hospitals in the North State that were on the list — some didn’t respond, but the ones that did explained that they’re not able to comment on how the Medicaid cuts will affect their services because they’re still assessing impacts.

Mayers Memorial posted a statement on Facebook about the federal budget bill, stating that it is “closely following the many changes and examining the potential effects” of the bill.

‘Nobody’s going to escape this’: Officials say impacts will be widespread

The federal budget bill will reduce Medicaid spending in rural areas by $155 billion over 10 years, causing 10 million people to become uninsured, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. Wheeler of CHA emphasized that most, if not all, rural areas in California will be impacted by the Medicaid cuts because they tend to have higher percentages of low-income people that rely on Medicaid than hospitals in urban areas.

But her biggest point of emphasis was that those impacts on rural hospitals will cause a wide range of trickle-down effects, not only in rural communities but also in surrounding areas. “Nobody’s going to escape this,” she said.

CHA officials explained how hospitals often act as anchor institutions to other businesses and services in less populated areas, with rural hospitals often being one of the biggest employers in communities. If hospitals close, many people lose their jobs, resulting in additional economic impacts to the community as people stop going out to eat and spend less at stores, they said.

Wheeler said people may also move away from rural areas if they lose their job or don’t have close access to a hospital or crucial service.

“When people have to start leaving their community to get those other services, they start to make decisions about whether they can stay in rural [areas], and then that has an impact, not only on hospitals, but every business in that community loses out,” she said.

The shift, she pointed out, can also lead to significantly higher wait times in emergency rooms that remain open.

“We cannot tinker with one part of [the system] and not expect that it will have an impact on another part,” Wheeler said.

It’s important to note, she explained, that these trickle-down effects will impact both uninsured and insured people alike — hospital closures hurt nearly everyone in the community, and insurance doesn’t prevent long wait times in emergency rooms.

Donnell Ewert, former director of the Shasta County Health and Human Services Agency, also weighed in on the issue. He said about 37% of the population in Shasta County is on Medi-Cal, meaning hospitals in Shasta County will be significantly affected. Like Wheeler, Ewert said this problem will impact everyone, not just uninsured people.

“Even if [people aren’t] on Medicaid … if their hospital closes, they’re still out of luck,” he said. “They’re still gonna have to drive 55 miles to come down to Redding or drive to Reno or whatever to get care.”

Amid fears and outcry over the federal budget bill a few months ago, the Rural Health Transformation Program (RHTP) was added by lawmakers to help mitigate the impact of Medicaid cuts in rural areas. RHTP will allocate $10 billion a year to rural hospital-related services throughout the country for five years.

Wheeler said the funds, which require an application process, would bring money into the state to help rural health care. But CHA spokesperson Emerson-Shea said this funding isn’t necessarily specific to rural hospitals — it’s for any kind of health care provided in rural communities, including telehealth. It also restores only a little over one-third of the estimated loss of Medicaid funding in rural areas.

Many California hospitals have already been struggling for years. According to an analysis by health care consulting firm Kaufman Hall, one in five hospitals in the state were already at risk of closing as of 2022, largely due to financial strain resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wheeler said CHA will continue working with hospitals in the state and try to bring their voices to the table when advocating for state and federal support.

“It’s going to be a challenging time for all of us, but we’re going to do this together,” she said.

Madison Holcomb is a recent graduate of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She’s reporting for Shasta Scout as a 2025 summer intern with support from the Nonprofit Newsroom Internship Program created by The Scripps Howard Fund and the Institute for Nonprofit News.

Do you have a correction to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org.

Comments (1)

Comments are closed.

Historically, the progressive and proactive response to public health took off when diseases like typhoid and cholera escaped the slum-like tenements of the working poor and began infecting the wealthy and middle-class neighborhoods. Taking health care from the poor will ultimately come back to bite you in the butt.