During community meeting on SB 43, Shasta families and clinicians discuss obstacles to seeking care

Senate Bill 43 expands the definition of a grave disability to include people with substance use disorder — making those with severe substance use eligible to be committed to care against their will.

In the lead-up to the passage of Senate Bill 43 last year, Californians debated its impact on human rights. The bill would broaden the definition of “gravely disabled” to include some people with substance use disorders, allowing California to force them into treatment against their will if they’re determined to be unable to provide for their basic needs.

The bill was opposed by California’s most influential disability advocacy organizations as well as the global nonprofit, Human Rights Watch. But municipal and county governments across the state endorsed it, as did several California chapters of the National Alliance on Mental Illness or NAMI.

SB 43 was passed two years ago as part of several legislative changes Gov. Gavin Newsom said would “overhaul” California’s mental health system. Individual counties were given until 2026 to implement it. In Shasta County, SB 43 will take effect starting Jan. 1.

This week, staff from the county’s Health and Human Services department held a community meeting to discuss the bill and how it will impact local residents. County workers, parents of children with substance use disorders, and care providers gathered to discuss current barriers to seeking adequate mental health treatment in Shasta.

Some brought up concerns about limitations in how the system currently responds to substance use crises, posing questions about whether these barriers will continue in spite of this new bill.

What is SB 43?

SB 43 builds on the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act (LPS) of 1967, which sought to end California’s practice of routinely institutionalizing people long-term — often in squalid, state-run psychiatric hospitals. By more narrowly defining the meaning of the term gravely disabled, the LPS Act sought to end the practice of routine institutionalization for people capable of leading rich independent lives with the appropriate supports.

The LPS Act legally defined the parameters of a grave disability as one which makes a person “unable to provide for their basic personal needs for food, clothing, shelter, personal safety, or necessary medical care” — whether due to a mental health disorder or alcoholism.

The wording of the LPS Act emphasizes the state’s need for careful balance between providing care where needed and ensuring freedom where possible.

”While the State may arguably confine a person to save him from harm,” the law states, “incarceration is rarely if ever a necessary condition for raising the living standards of those capable of surviving safely in freedom, on their own or with the help of family or friends.”

A half-century later, SB 43 was passed. The new law adds to the LPS Act’s definition of the term gravely disabled, adding substance use disorder to the root causes that may qualify someone for involuntary institutionalization due to their inability to provide basic self-care.

Under SB 43, people who meet this criteria — as determined by law enforcement officers or mobile crisis response teams — can be held without their consent in a hospital. Those involuntary hospital stays occur under what’s known as a 5150 hold and can be extended with the signature of a physician for up to 14 days under a 5250 hold.

Both the LPS Act and SB 43 also allow individuals who meet the state’s criteria for a grave disability to be forced into a conservatorship by county courts, placing their decision-making power in the hands of others, long-term.

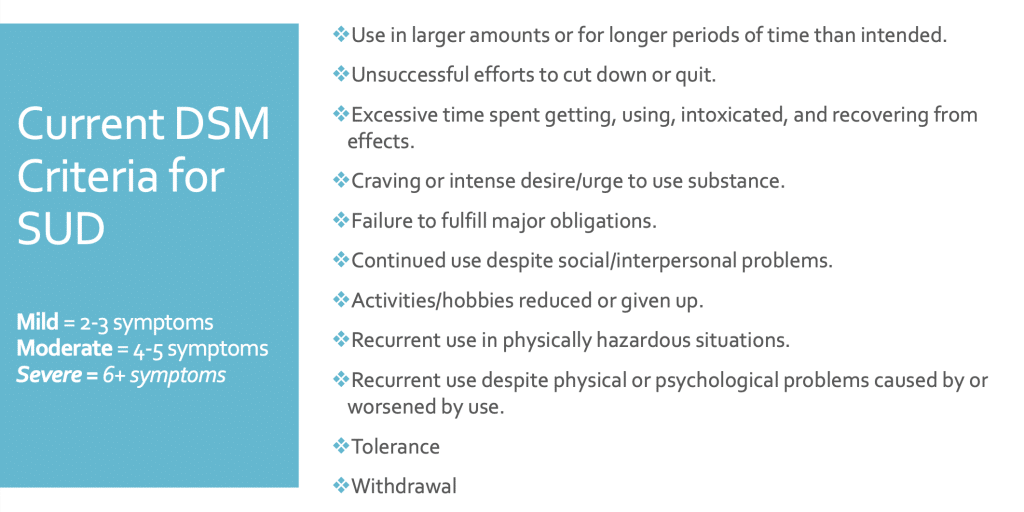

HHSA’s Clinical Division Chief Genell Restivo explained during this week’s community meeting that only those whose substance use has reached a level so severe that is impacting their ability to provide for their basic personal needs would qualify under SB 43. That level of severity is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

One voice among the crowd during Thursday’s community meeting was a mother who shared a personal story about her daughter’s acute methamphetamine use disorder. She expressed her extreme frustration with the Redding Police Department, the courts, and the conservatorship system as all incapable of moving her daughter toward help, saying she’s unsure if the new criteria under SB 43 will help.

Ethical debates over SB 43

While SB 43 can place people in conservatorships against their will, the process of doing so is extremely complex involving multiple systems and individuals, including healthcare providers and the courts.

Those decision makers must weigh the harm someone may be posing to themselves against their rights to freedom and self-determination HHSA’s Restivo explained, saying those personal liberties “oftentimes get in the way” of the county’s “just swooping in and saving the day,” for the families affected.

The debate over preserving patient rights versus upending them is why SB 43 has been controversial since its inception. Samuel Jain, a senior mental health policy attorney at Disability Rights California, told Shasta Scout that he believes the bill “erodes the civil rights of people with mental health disabilities.”

He is critical of legislation that can create long-term risks for loss of liberty during peoples’ moments of greatest need — at crisis points which are often caused by the community’s failure to provide basic preventative care. “One of the biggest things we see in the constituents that we talk to,” Jain said, “is people don’t actually have access to upstream services that they need before they actually end up decompensating and needing involuntary treatment.”

“In LA County, the waitlist [for psychiatric medication] is like three months… You know, they put you on a three month wait list before you can actually see a provider and get those medications,” Jain pointed out, adding that compounding factors like unstable housing often exacerbates people’s health conditions.

Adding more people with SUD into the pool of patients already subject to involuntary institutionalization will strain the current system even more, he said, as communities are already struggling to adequately respond to people in psychiatric crises. And involuntary commitment to locked facilities for care — in many cases at medical centers hundreds of miles from home — is also often a traumatic experience, Jain explained, that can worsen existing mental health and substance use factors.

During the meeting this week, HHSA’s Restivo referenced these infrastructural challenges, saying that SB 43 is a state mandate rather than a solution and emphasizing that Shasta has to do the best it can for the community under current law.

HHSA’s responsibilities do not change under SB 43, although its client pool may expand. The agency will refer qualifying clients to substance use disorder (SUD) medication-assisted treatment programs, the agency confirmed by email, but noted that HHSA does not operate any inpatient or locked facilities that can provide this service.

Speaking from the perspective of a first responder, John Luoma, the program manager of Hill Country Community Clinic’s Mobile Crisis Outreach Team (MCOT), believes that SB 43 could ultimately improve people’s outcomes in how they access treatment options for severe substance use disorder.

Designated members of local mobile crisis teams respond directly to people in the midst of a mental health crisis, and are permitted to issue 5150 holds and take people to emergency rooms.

“In the past, many individuals ended up in jail simply because there was no alternative structure to hold them safely,” Luoma said. Because of that, people with substance disorders who were found to be on the brink of injury or even death, he said, could be taken to jail on charges of public intoxication, if mobile crisis members couldn’t convince them to voluntarily seek treatment in the moment of crisis.

Addressing the potential strain that additional SUD 5150 holds could have on the local healthcare system, Luoma said it’s possible that emergency departments could feel an initial increase in pressure with added substance use-related 5150 holds. “But the alternative — continuing to route people with severe substance use disorder through the criminal justice system — carries its own harms and costs.”

He also expressed hope that the proposed True North behavioral health facility, if funded by the state, could relieve some of that strain in emergency departments.

“Does [SB 43] have the potential to erode civil liberties? I think the very objective answer to that is yes it could,” Luoma said, acknowledging that concerns over the suspension of those rights are valid.

“But given the system that we have … My expectation as to what will happen is not that more people will be detained, but that they’ll be detained in a way that prioritizes their health and their recovery, versus prioritizing public safety and then being contained in an incarceration setting.”

Do you have information or a correction to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org.

Comments (10)

Comments are closed.

Senate Bill 43 will open the door to criminalize not only those with substance use disorder but homelessness as well. Being homeless is NOT A CRIME!

Substance use disorder? You mean drug addict.

This was taken from the California state portal website:

“WHY SENATE BILL 43 WAS NEEDED: Under existing law, people may be eligible for a conservatorship if they have a serious mental illness that leaves them unable to secure food, clothing or shelter. Senate Bill 43 broadens eligibility to people who are unable to provide for their personal safety or necessary medical care. In addition, Senate Bill 43 encompasses people with a severe substance use disorder, such as chronic alcoholism, and no longer requires a co-occuring mental health disorder. The new law will update the situations when this intervention can be considered and create the first-ever meaningful transparency into data and equity on mental health conservatorships.”

There is more on this site about how sb43 protects people’s rights while at the same time giving them the protection that they need because of their serious mental illnesses. These are brain disorders and people are unable to realize that they are ill because of a chemical imbalance or brain injury. Jail is not a healthcare facility and is a dangerous place for people with mental illness.

Very informative! Thanks.

And we should stop saying “drugs and alcohol.” It’s all just drugs.

This article and the ongoing debate over True North really set me up to be the grinch but here we go again: do not call it a “substance use disorder” please. Have the courage to call it what it is and make people/families take responsibility. Childhood leukemia and cleft pallet are not equal victims with a “teenage junkie.” (And completely miss me with the young adult nonsense). Now if we’re talking about streamlining the process to institutionalize crazy family members, lets go. Perhap we could augment the shuttering of Susanville and create a ward. Jobs and beds. Like his and hers and theirs bathroom on all prison properties— clipboard prison guard checks you in— violent lifers, door on the left. Homeless crazies and tweekers, door on the right. Everyone is out of the parks and out of the rain, getting help or doing time.

Needs to be some personal family responsibility to keep your kids off drugs.

Could not agree more… Poor life choices… Just need to tell Trump and Republican party that as well and lay off the drug boats going to Europe, not America

Let’s get the Europe boats too.

Let your pal Putin do that