Open Notebook: On Covering the Police

Our Open Notebook series offers readers a behind-the-scenes look at how our journalists work. In this Notebook entry, reporter Nevin Kallepalli shares what he’s learned about justice from reporting on the police.

View of downtown Manhattan from the roof of my building in Chinatown in March of 2020. Photo by Nevin Kallepalli.

In the weeks after George Floyd was murdered on camera, I called my parents from my shoe box apartment in Lower Manhattan. My father was horrified by what he was seeing in the news – footage of the National Guard firing “less than lethal” rounds at a Minneapolis woman standing on her porch, a reporter blinded by riot police, and the deployment of military–grade vehicles on otherwise quiet streets of the Twin Cities. This national state of emergency was not something he ever expected to witness in the United States.

My parents immigrated here from South India in the 1980s, and hadn’t thought, perhaps naively, that America’s “rules–based” justice system was capable of manufacturing the crisis unfolding before us. Nor did they expect the people to actually burn down their streets. The disorder of the moment seemed reminiscent of where they came from, but with a caveat.

“India is not like America,” my mother scoffed. “Because in India, nobody becomes a cop because they want to help people.” She found that idea ridiculous. The term “police brutality” in the Indian context was redundant, as the purpose of the police was to brutalize people on behalf of a corrupt political system, or frankly, whoever was paying. Then and now, curfews, crackdowns, and extrajudicial killings are not uncommon. In the darkest chapters of Indian history, the police did the opposite – nothing – as lynch mobs tore through Muslim or Sikh neighborhoods of the country’s largest cities.

That summer in 2020 was hotter than others, and not just because I lived on the sixth floor of an old tenement, where the rising heat of 20 kitchens below me got trapped in my unit. The city was pissed and so were the cops, and there was nowhere for the steam to escape.

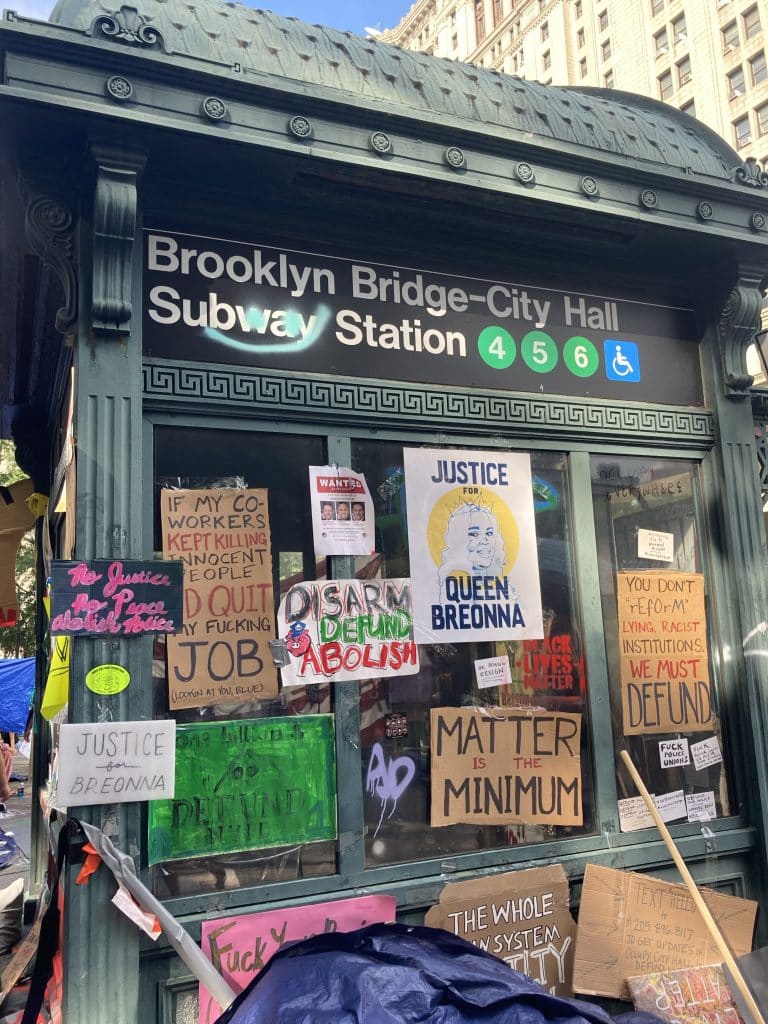

It felt taboo to look officers in the eye as they idled on every corner, especially so when one parted a makeshift barrier to allow me entry onto the street where I paid rent and taxes. It was grating. It was sometimes humiliating. And it was the first time many city residents (myself included) got a taste of life under constant surveillance, something New Yorkers in the projects a couple streets over had known intimately for generations. My bedroom was just a few thousand feet away from city hall, where midnight stand offs erupted between protestors and NYPD officers in tactical gear. When I couldn’t sleep through the noise, I skipped down the six flights to observe the chaos from the sidelines.

This is how I remember it. I’m sure I would remember it differently, if back then I was a reporter. I hadn’t the vaguest idea of how the system actually worked, but what I saw seemed clear. Unarmed masses kettled together by blue men and blue women with rubber bullets, batons, and pepper spray.

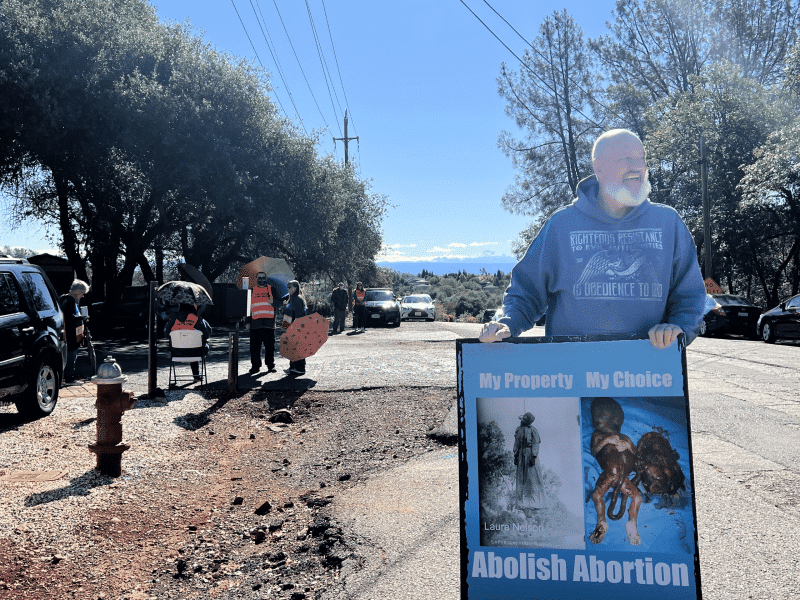

Meanwhile, in rural Shasta where I would land five years later, 2020’s lockdown and subsequent protest movement have forged fissures that are still felt today.

One of the first law enforcement stories I ever wrote was for Shasta Scout, just months after moving to Redding from New York and more than a year after receiving my graduate degree in journalism. In January 2025, a 27-year-old man named Juan Moreno was found dead in his cell at the county jail. My reporting started with a press release from the sheriff’s office with scant details. With little to go on, our final piece wasn’t much longer than the county’s opaque announcement of the tragedy. But while scanning the jail’s online list of inmates in custody, I saw a detail that leapt out at me. He was awaiting trial. This young man’s life was cut short late one winter night, but so too was his presumption of innocence, cut short every day he spent behind bars while waiting to appear in court.

The presumption of innocence is precious, but dangerously fragile, as articulated by a legal scholar I interviewed for my first investigation into the Redding Police Department’s conduct on social media. To me, the presumption of innocence is an almost spiritual credo, a kind of faith that insists on the good in people despite the circumstances that have brought them into a courtroom. This principle is not antithetical to police work or prosecution. After all, without presuming someone is innocent up until the moment the threshold of “reasonable doubt” has been crossed, a guilty verdict itself carries no weight. In reality, this may rarely be achieved, but to me, striving toward this ideal is the closest thing we have to freedom.

Reporters are not legally bound to the same presumption of innocence when it comes to our subjects, even if our goals are largely in line with those of the ideal criminal justice system: the pursuit of truth. Many reporters take advantage of this, depending entirely on communications from police departments for a quick and juicy scoop. Salaciousness is mistaken as hard hitting truth in those stories, produced in flash, that note little difference between allegations and actual guilt.

Nor are we bound by the same timelines as the courts. A crime occurs and news outlets report on it immediately with only the partial information available to them. Rarely do journalists follow through to the very end of a case, which could go on for years until a verdict is delivered. Is the suspect named in an initial press release found innocent? Guilty? Or more often, they took a plea bargain before a trial could begin, which in itself is not necessarily an indicator of innocence or guilt either.

Covering crime is easy, if you stop short of actual reporting. When reporters act more like stenographers, repackaging a law enforcement press release in the form of news, the narrative framework is already baked in. There is a good guy and a bad guy, a tragedy, and all too often a lurid ending. These stories stoke fear and indignation. They generate traffic. They keep readers coming back.

What if reporters were bound to the same legal standard as prosecutors and defenders? Or at least, tried to find ways to recreate the conventions of the courtroom on the page. There are obvious limitations to this. We can’t subpoena suspects, or examine evidence before it goes to discovery, and we have to turn around stories for our readers with the same limited details as most of the general public. So what I mean by “actual reporting” is adding context, while maintaining a fundamental Constitutional principle: those accused of a crime, no matter how heinous, are still innocent until proven guilty.

In the relatively rare instances in which we do cover crime at Shasta Scout, my editor Annelise and I look at a suspect’s history with the criminal justice system, talk to their family when possible, examine California penal codes, and situate the narrative within a birds eye view of crime and incarceration data across the state. We do not treat suspects as antagonists and police as protagonists, or the other way around. We simply try to gather as much information as possible and leave judgement to the readers, who in this configuration, are the closest thing to a jury.

A press release from a city or county is only a fragment of the story, just as the prosecution is only one element of a criminal proceeding. In the abstract, the American justice system has a beautiful symmetry that indisputably extends the right to a fair trial to every person who enters a courtroom – regardless of allegation, citizenship status, or how much money a defendant can pay for their legal counsel. The least we can do as reporters is uphold that symmetry in the way we tell stories.

In early spring, Annelise asked me if I’d like to sign up for Redding Police Department’s “Citizens Academy.” The academy is a nine week course free to the public, facilitated by officers from nearly every sector of the department from SWAT to admin. The stated purpose of the course is to cultivate “advocates” for the police among the public in Redding, though based on the sentiments shared by other students, such a class is hardly required to encourage pro-police advocacy. Most of my classmates, all adults with a variety of backgrounds, signed up because of their already-ardent support for officers.

What we were shown during the class was clearly intended to confirm what many people already know: that officers are human beings subject to mistakes like anyone else, often working under extremely stressful conditions. The same kind of nuance was rarely extended to the people who commit crimes, whom officers consistently referred to simply as “the bad guys” during lessons and trainings.

It is not my job as a reporter to advocate or not advocate for the police – or any government employee for that matter. Certainly, of any sector of civic life, police departments are probably the most scrutinized in the media, for the reason that they are arguably the most powerful. It is undeniable that most city budgets skew heavily toward law enforcement, and the operations of police departments are generally the most shielded from public view. With great power comes great accountability, and if I am to take on that task I could stand to learn a thing or two from officers on their own turf. And the class turned out to be an extremely enriching experience.

I was less gripped by officer’s tales of action-packed arrests, and more by the granular state penal codes and strict regulations to which they are legally bound. I learned that with every crack of a taser, bite of a canine, or bullet fired (metal or rubber), there should be a detailed record. I went on a ride-along with a policeman as he made a routine arrest of an unsheltered veteran for failing to meet with his probation officer, a setting far more illustrative of this small community’s core dysfunction than some guns-out, high stakes situation. Inevitably, spending that much time with any group of people will humanize them. I certainly confronted many of my own biases and assumptions of what could happen behind closed doors at Citizen Academy. But getting to know a more personal side of the men and women at RPD will never shift the outcome of my reporting, even if it completely changes the way I go about it.

This came to a head on March 26, when an RPD officer named Bailey Odell shot a man named David Schaeffer in the parking lot of a Safeway on Cypress. Ironically, this occurred less than a week after my introduction to Citizen Academy when the class was introduced to body-worn cameras. For the first time in my nascent career, I rushed over to a crime scene with my editor, and was immediately greeted by Lieutenant Jon Sheldon, someone I knew from class, a connection which completely changed the tenor of reporting on that day. As the days passed, through community tips and records requests, we were able to determine the identities of both characters in the story, officer and suspect, before the police were willing to disclose any information. We combed through court records, talked to witnesses, and importantly, interviewed Schaeffer’s family to complicate the flattened image of pure criminality projected onto him in law enforcement briefings. We did it all while I was attending weekly classes taught by police officers, who may or may not have been on the receiving end of my many requests for documents.

I felt like I was seeing this story from two perspectives, inside and out. In keeping with the ethos of simulating the courtroom through our reporting, a police shooting presents a strange challenge: treating both the officer and Schaeffer as innocent until proven guilty, or perhaps more aptly, not assigning clear culpability to either. It is a fact that Odell shot Schaeffer. It is a fact that Schaeffer drove away from Odell, a clearly marked police officer with his weapon drawn. Where the truth of the matter lies is in the subjective details no one else can know for sure; did Odell fear for his life, the legal standard for which officers are permitted to fire their weapons at civilians? Was Schaeffer trying to physically harm the officer when he drove toward him, or was he simply panicked at the sight of the gun?

This is the strange thing about being a journalist – it comes extremely close to the legal process without any of the actual power. At times it can feel totally impotent. But reporters also have the responsibility to interrogate the legal system from the outside, which is perhaps the highest standard of justice at civil society’s disposal, even as it chronically falls short. In this way, the journalist bears a special power. Yes, we cannot deliver a judgment. But we can shed light.

We use our Open Notebook series to invite you into journalists’ work by sharing some of our internal processing: what’s fascinating us, what we’re learning, what’s motivating our work, and what’s concerning us. The comments are a place where you can share your new ideas, alternate perspectives and criticism for our assumptions. We believe this kind of collaboration between reporters and readers leads to stronger journalism and a stronger democracy. Thanks for being here and for collaborating with us! Read more about our Open Notebook project here. You can also email us at editor@shastascout.org.

Comments (5)

Comments are closed.

Reading your article I felt gratitude for Shasta County having a truly dedicated, sharp journalist. Enjoyed learning of your experiences. It was a true pleasure to read your excellent writing also.

Great article that was very well written Nevin.

Thank you, Nevin Kallepalli, for this thoughtful, insightful article. Your news reporting here in Shasta County has been a very positive addition to our ability as readers to stay informed.

Excellent article! Another LE eye-opener is a class offered periodically: Force Options Training. It offered all the participants an opportunity to understand the split-second decisions officers need to make as to the degree of force necessary in various situations. It became even more understandable when we were placed in similar situations ourselves. Highly recommended!

Very well done, Nevin. Having lived here off and on for 50 years, I have seen some very wild West actors, both citizens and peace officers alike. And even recently, as Shasta County CEO threatens me in BOS meetings with arrest (sometimes deservingg, yes) I still have a great relationship with the Sheriffs I have had the privilege of meeting. Like all people, there are peaceful peace officers and some officers that should not be on the job. I discourage people from insulting officers and the whole blanket mantra that L.E. our friends is not cool. Thanks for the good personal perspective you provided.