Feather Alerts Denied: California’s Efforts to Locate Missing Indigenous Relatives Needs Reform, Native Families Say

Similar to the Amber Alert, the newly established Feather Alert system was meant to be a vital tool for Native families searching for missing relatives. Native policymakers and families say law enforcement agents are unnecessarily rejecting the majority of Feather Alert requests. Amendments to the law are already in process.

Some researchers have identified Northern California as an epicenter of what’s known as the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and People (MMIWP) crisis.

Family testimonies as well as research suggest the region is a particularly dangerous place for at-risk Indigenous women and other relatives. According to a 2020 study by the Yurok Tribe and the nonprofit Sovereign Bodies Institute, there have been 105 documented MMIWP cases in the area, a number that means Northern California would rank in the top ten if it were its own state.

Last year, Northern California Native families thought they had gained a new tool to help locate their missing relatives. But a new state-wide law enforcement broadcast system, known as the Feather Alert, hasn’t worked as well as they’ve hoped.

Feather Alerts are used to distribute information about missing Native relatives to broadcasters, social media, digital billboards and other outlets across the state to raise awareness about the search for missing relatives. The California system functions very similarly to the national Amber Alert system, which is designed to help locate missing children.

But Native families say they’re being unnecessarily denied access to this important tool because law enforcement agencies have been rejecting their requests for Feather Alerts even when their missing relatives are seriously at risk.

Under the current law, local law enforcement agencies evaluate Feather Alert requests from Tribes or Native families to decide whether a Native person is seriously endangered enough to merit an Alert. If approved at the local level, the request for a Feather Alert is sent to the California Highway Patrol, which makes a final decision on whether it meets legal criteria to be disseminated around the state.

Native advocates say this subjective evaluation process has led to a high rate of rejection because of law enforcement’s ignorance, or bias, about the nature of the MMIWP crisis and the realities of Tribal communities.

Assemblymember James Ramos (D-San Bernardino), who authored the original Feather Alert bill, agrees. According to Ramos, law enforcement agencies have denied about sixty percent of Feather Alert requests since Jan. 1, 2023. Ramos’ staff supported that statement for Shasta Scout with statistics showing that only six of the fourteen requests for alerts sent to the California Highway Patrol by various local law enforcement agencies resulted in a Feather Alert being sent out. CHP has not responded to multiple requests for comment on the reasons for those Feather Alert denials.

And those statistics represent only part of the issue. They don’t include Feather Alerts requests made by families across the state to local law enforcement jurisdictions if those requests were turned down by local law enforcement and never sent to the CHP for review. It’s unclear how many of those requests have been made state-wide, and how many received a formal assessment by the local jurisdiction.

Native policymakers and advocates are already working on changes to the Feather Alert policy. This March, they introduced Assembly Bill 1863, which would amend the process to reduce law enforcement’s discretion.

The bill would also reform the Feather Alert law to prioritize the sovereignty of California Tribes and reinforce the importance of Native families’ assessment of their missing relative’s risk. It passed California’s Assembly on May 22 and is currently being reviewed by Senate committees.

Tribes and Native families and advocates say giving more power in the process to Tribes is an appropriate way to center their intimate knowledge of each unique relative’s situation and the complexities of the distinct Tribal communities they’re a part of.

Morning Star Gali, a Pit River Tribal member and founder of the non-profit Indigenous Justice, is hopeful that the changes proposed to AB 1863 will make a difference, if they move forward.

“I think the amendments are going to be helpful,” Gali told Shasta Scout. “There is just a lot of education that needs to happen to orient (law enforcement) to the Feather alerts and that a Tribe’s request for Feather Alerts should be granted based on the Tribe’s own criteria.”

MMIWP Crisis Informs Amendments to the Feather Alert

The Missing and Murdered Women and People (MMIWP) crisis is a term used to describe how Native people, especially women, are far more likely to go missing or suffer violent deaths. More than 5,712 cases of Native women and girls were reported in 2016 by the National Crime Information Center.

The unusually high rate of missing and murdered Indigenous women is attributed to a variety of factors, including the lingering impacts of historical trauma on Indigenous communities and gaps in the criminal justice system, including a significant lack of data collection on missing Native people.

Currently, a Feather Alert can only be issued if the disappearance “appears suspicious” and law enforcement believes that the person is in danger, that the broadcast will aid the investigation, and that they’ve already used all available local and tribal resources to find the missing person.

Once the Feather Alert request is sent to CHP, that agency must also agree that the request meets the criteria before issuing the Feather Alert.

A key proposed change to the Feather Alert law would drop the requirement that law enforcement must determine the Native relative’s disappearance to be “unexplained or suspicious,” reducing the likelihood that bias or ignorance of Tribal cultures would affect the decisions.

The new amendments would also give Tribes, as well as local law enforcement, the authority to request a Feather Alert directly from CHP. CHP staff would still need to confirm that the request meets the new Feather Alert criteria.

Feather Alert Criteria and Historical Indigenous Trauma

The new language of the bill also refashions the Feather Alert criteria so a missing person’s mental health or substance use challenges are seen as more, not less, of a reason to believe they could be at risk.

Gali, the founder of Indigenous Justice, said many Native families report that law enforcement staff use a missing person’s history of substance and mental health issues to decline sharing a Feather Alert.

It’s especially important to address this bias, Native families say, because mental health and substance use struggles are directly tied to the MMIWP crisis and are risk factors for going missing or suffering violence in the first place. And many of these struggles are rooted in the lingering harms Native families continue to grapple with as a result of genocide, Indian boarding schools and forced displacement.

“A refusal to issue the alert for anyone who has a history of mental health or substance (issues) shows an incredible lack of understanding for the history of California Indian peoples, and why there are so many struggles,” said Gali, “It is also absolutely a violation of Tribal sovereignty.”

Law Enforcement Bias and Local Native Disappearances

Shasta Scout interviewed seven Native community members for this story. They said bias by law enforcement goes deeper than the Feather Alert denials and is a root cause of the broader MMIWP crisis itself.

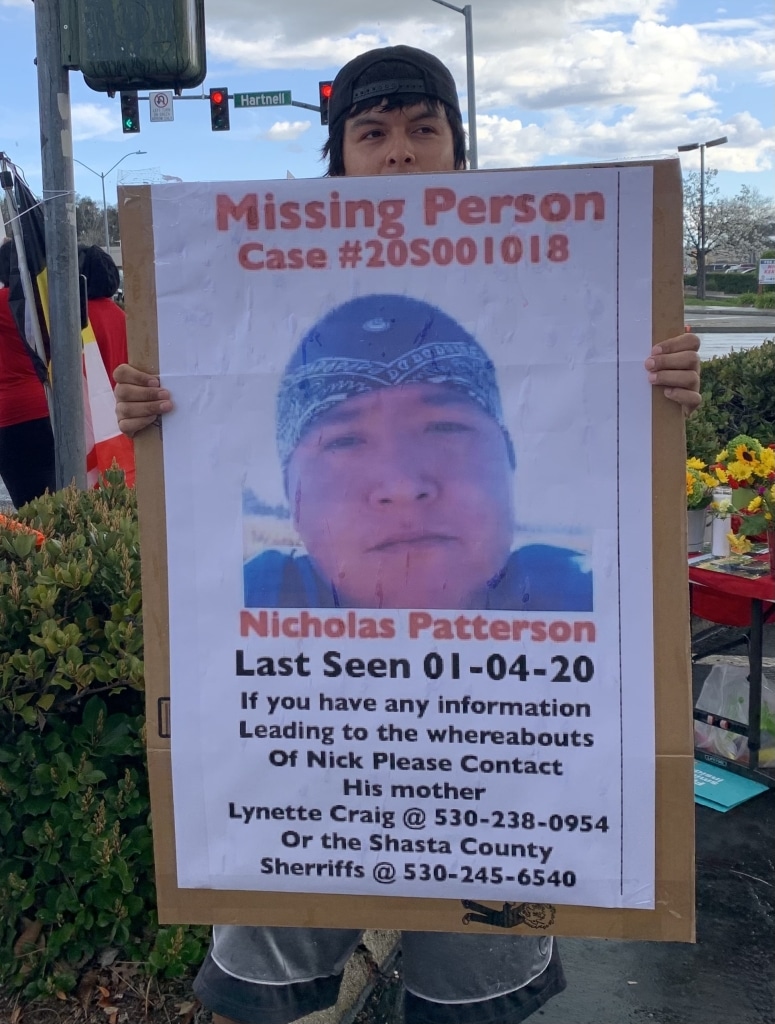

When her nephew Nick Patterson, a Pit River tribal member, went missing near Burney in January of 2020, Lisa Craig said Shasta County Sheriff’s deputies resisted taking his disappearance seriously. Although Nick had been struggling with substance use issues, Craig said the family knew it was extremely unlike him to go silent and avoid important family gatherings. But, she said, law enforcement didn’t take their family’s understanding of Nick seriously.

“They told us “Well, he is part of that ‘crowd’, and he could have just taken off. He’s an adult.’” said Craig. “We kept reiterating that it wasn’t like Nick to not get ahold of his family. For them to disregard our concern, it was very frustrating and disheartening.”

Patterson remains missing, and the lack of closure continues to take an emotional and spiritual toll on his family, Craig said. The investigation by the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office is still ongoing, according to Tim Mapes, Public Information Officer.

While sensitive details about a case may not be shared with family members for the sake of the investigation, Mapes said the Sheriff’s Office understands the “emotional toll a missing loved one takes on a family and our investigators work diligently to resolve cases and bring about closure.”

But several investigations into the MMIWP crisis have found Native families regularly report law enforcement as “skeptical, uncaring or minimizing their loved one’s disappearance,” according to the Sovereign Bodies Institute.

In a report produced by the Yurok Tribe and SBI, they recommend that law enforcement should assume the missing person needs immediate assistance and is in danger until proven otherwise. They also say every agency should have a specific MMIWP protocol that outlines how to respond to the report of a missing Native family member. Both the Redding Police Department and the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office responded to questions from Shasta Scout by saying they do not yet have a specific MMIWP protocol in place.

April Carmelo, a local Native educator and City of Shasta Lake resident, said she experienced similar resistance when her sister disappeared from Red Bluff in 2013. She said officers with the Red Bluff police told her it wasn’t a crime for an adult to go missing and said they resisted doing a welfare check on her sister at her home. The remains of Mary Carmelo were eventually recovered in Plumas National Forest, and her death is being investigated as a homicide, which remains unsolved.

“The problem is (law enforcement) doesn’t trust the instincts of the family members to know when something’s not right. Like they don’t believe us.” said Carmelo, who is a citizen of the Greenville Rancheria and of Wintu, Maidu, Tongva and Ajcachemen descent.

Asked to respond to Native families’ concerns about the Sheriff’s Office’s responses to their missing or murdered relatives, Mapes wrote to Scout that the Sheriff’s Office treats all missing person cases with “the utmost seriousness and responds to them without delay per California law.”

During the Gold Rush era in Northern California, state-sponsored militias, vigilantes and U.S. military forces waged a campaign of removal and extermination against Native peoples, who they saw as less than human and destined to go extinct.

This era so normalized violence against Native people that it still permeates modern society and the criminal justice system, contributing to the MMIWP crisis, Native scholars and advocates contend.

The dismissive attitude Native families say they experience from law enforcement can trigger these memories of the region’s violent past.

“It makes me think nothing has changed. They still think a ‘good Indian is a dead Indian.’” Craig said.

Do you have a correction to this story? You can submit it here. Do you have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org

Comments (4)

Comments are closed.

Tribal leaders need to continue taking their case to legislators in SAC, don’t give up, press them for meaningful legislation. As well go to each city council in Shasta Co. and request that a formal resolution be enshrined that they do not condone actions against native persons and that they need to create their own Feather Alert system.

Same for Board of Supervisors, go there !

Treadway: Just a suggestion that ordinary white people could also advocate for meaningful legislation that benefits the Tribes.

Hi Frank,

We didn’t have space to address it, but Tribes, activists and Native policymakers have been very active at the Capitol the last few years on the MMIWP issue with a great deal of success. Several bills are in the pipeline, and the state recently awarded $20 million in grants to Tribes to address the issue – https://www.sacbee.com/news/equity-lab/representation/article289987954.html

Several sources told me that MMIWP has been a unifying issue for Tribal organizing because it affects so many of their community members, so the organizing has been really strong.

Heather Haller went missing years ago and because she was native and hung out with that “crowd” they never took her seriously either. There have been so many devastating things happen within different family units that the missing people come from, we know the cops don’t give a s***