In Northern California, Lynette Craig is still fighting to find justice for her Native son in a broken system

After his disappearance in 2020, Nick Patterson’s mother said she received only limited help from law enforcement. The lengths she went — to discover the truth and recover the rest of her son’s body — illustrate the profound systemic failures Native families face in the search for their missing and murdered relatives.

When Lynette Craig went to pick up her son Nick Patterson’s remains at a mortuary in Modoc County, she wasn’t sure how to feel. It was earlier this spring, and over a year since his partial remains were first recovered.

“He was a big boy,” she said. “It was just weird to me, because my big old boy fit in this little box. It made me mad, but at the same time, it was good to hold him again.”

Craig is a member of the Pit River Tribe, whose ancestral homeland is located in Northern California. When she got her son’s remains back, she was glad she could finally bury him, an important aspect of tribal tradition that allows the deceased to journey on to what’s next. The long-awaited moment came after what she says has been a years-long struggle with local law enforcement to push Nick’s case forward.

Nick, a member of the Atwamsini band of the Pit River Tribe, went missing more than five years ago in January 2020 when he was just 26. While some of his remains were finally found last year, the reason for his disappearance and death remains unsolved, leaving his family and friends still searching for answers.

His mom’s battle for the truth captures determination fueled by the profound grief of a mother who lost her child. But it is also emblematic of the structural challenges Native people often face when working with law enforcement and the ongoing systemic negligence that’s been documented in response to Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP), whose cases are seven times less likely to be solved than those of non-Native people.

Craig said she’s seen the effects of the MMIP crisis in her own Tribe. She recalled going to a funeral of an Indigenous child who went missing decades ago, Little George Montgomery. His body was dismembered, and all that was left was his skull, which was placed in a small box for his wake.

“I just remember thinking, ‘Oh my God, that’s horrible. Nothing like that will ever happen to me,’” Craig recalled. “But now I have my own box.”

It wasn’t until Nick’s disappearance that Craig truly realized the gravity of the MMIP crisis, particularly in California, home to the largest Indigenous population in the United States.

“That’s one thing that kind of disturbs me, is it had to hit home first for me to realize and to really pay attention to what’s really been going on,” she said.

California has made efforts in recent years to allocate resources toward the MMIP crisis, awarding millions of dollars to tribes to support MMIP investigations, including a grant to the Pit River Tribe last year.

The state also established the Feather Alert system in 2022. Similar to the AMBER Alert, the system helps locate missing Indigenous people by prioritizing visibility for their cases. California State Assemblymember James Ramos, the first and only Native lawmaker in the assembly, also pushed a bill in 2020 that directed the state Department of Justice to increase law enforcement collaboration for MMIP cases.

But the related issues are complex and take time to solve. For example, a component of the Feather Alert system that allowed for subjective decision-making initially led to a high rate of request denials by law enforcement agencies. The issue was addressed last year by an amendment, which aims to reduce law enforcement’s discretion in which cases to flag for alerts.

The struggle to get answers from law enforcement

Craig describes her son as a respectful and generous person. He played basketball, was an active member of his Tribe, gave enormous hugs and loved The Rolling Stones. Nick swore his purpose in life was to be a big brother, and he was known to always have his hand out to help others.

“Whenever anybody seen Nick Patterson come in, they had a smile on their face,” Craig remembered. “They genuinely cared about him.”

He was last seen on Jan. 5, 2020. A few days after he went missing, Craig filed a missing person report with the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office, which has jurisdiction over the area where her son went missing. She says she felt the office did not take Nick’s case seriously or handle it with enough urgency from the start, explaining that they asked if Nick just needed some time away or if he was out drinking, even after Craig assured them that it wasn’t like him to disappear without telling anyone.

Craig said she requested that the sheriff use cadaver dogs to search for Nick, but the department claimed they couldn’t use the dogs until 30 days after the missing person report was filed. Later, while attending MMIP conferences, Craig was told that there is no waiting period to be able to use cadaver dogs. Neither the Shasta Sheriff’s Office nor the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training list any such restriction in its policies.

A few months after Nick was last seen, in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Around the same time, the Shasta Sheriff’s Office transferred Nick’s case to the Modoc County Sheriff’s Office, which oversees the area where Nick resided at the time he disappeared. Craig claims the Shasta Sheriff’s Office wouldn’t release Nick’s official investigation records to Modoc — something neither the Shasta nor Modoc Sheriff have confirmed nor denied.

“Ever since he went missing, I’ve hit every roadblock, every obstacle that there is,” Craig said. “It’s just stupid, like, unimaginable.”

The Shasta Sheriff’s Office refused to answer a list of specific questions for this story, including requests to learn more about the department’s reportedly dismissive behavior toward Craig when she filed the missing person report and the alleged 30-day rule to use cadaver dogs, as well as claims about whether the investigative files were ever transferred to Modoc.

Instead, the Shasta office repeated a vague general statement about the case that’s been provided to the press in the past.

“The Shasta County Sheriff’s Office treats all missing persons reports with the utmost seriousness and responds to them without delay, as required by California law,” Public Information Officer Tim Mapes said in an email statement. “We do so without bias or discrimination, regardless of a person’s gender, race, ethnicity, religion, or background. Every report is evaluated and acted upon with the same urgency and commitment to public safety.”

Many Native people distrust law enforcement for a variety of historical reasons, chief among them America’s history of government-endorsed violence against Native people and subsequent forced assimilation.

Federal laws enacted in the years that followed the massacres of tribal communities across Northern California furthered the harm against Indigenous people, laying the groundwork for the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People crisis occurring today. Public Law 280, for example, has sometimes allowed crimes against Native people to go unaddressed since it required tribal police to share criminal jurisdiction with state police, causing overlap and confusion.

Despite these substantial issues, tribal communities, like others, remain reliant on the help of police when seeking justice. Craig said the complexity of navigating that relationship is something she came face-to-face with while working on Nick’s case.

“I wasn’t sure what I was gonna have to do to keep his case under investigation but be able to do it in a way where I wasn’t gonna be stepping on their toes, because I still need their help,” she said.

Modoc Sheriff Tex Dowdy, himself a member of the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, said since his office took over Nick’s case in March 2020, “numerous leads have been followed, and multiple interviews have been conducted” in the investigation.

But Craig, who still thinks not enough has been done to solve Nick’s case, said it became increasingly clear to her over time that she would have to take matters into her own hands to make progress in finding the truth.

Over the last few years, Craig has gathered records to aid in Nick’s case, facilitated communication with experts and officials and organized a grid search, which occurred this past June, to look for more of Nick’s remains — in effect, taking on the duties of an investigator, without training or compensation.

In 2023, Craig consulted the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) website and read that dental records and/or DNA samples are pivotal for identifying people in missing person cases.

It occurred to her that neither of the two sheriff’s offices had contacted her to collect this information, although, according to a Shasta County Sheriff’s Office policy, this information should have been collected shortly after Patterson’s missing person information was reported to the state’s Department of Justice. Craig checked Nick’s file on the DOJ site and saw there were still no dental records or DNA included.

Reading through the information on the NamUs site to learn how best to help Nick’s case was one of many emotionally challenging parts of her efforts to find him, Craig said.

“When I tried to register Nick for NamUs, I still had high hopes that I would find my son alive, safe and in one piece,” she said. “When I started reading on the website about human remains, what it was all about, it took me probably two weeks to finally sit down long enough to register with NamUs.”

Craig took the initiative to contact the California DoJ’s Office of Native American Affairs to request a family reference sample, which is used to help identify missing persons through DNA. Extra steps had to be taken to get the kit sent to Nick’s dad, who was in prison at the time.

“I needed these tests done because I knew that Nick wasn’t around anymore,” she said. “There was no way to identify Nick if we did find him.”

Craig also tracked down Nick’s dental records, but it wasn’t without struggle. She said Nick rarely went to the dentist because of how good his teeth were, and his orthodontist, who was based in Oregon, sold his practice. She was eventually able to get a hold of the records so that they could be included in Nick’s file.

Finally, on April 24, 2024 — more than four years after he went missing — a skull and humerus bone were found by a civilian in Lookout, a small and remote area in Modoc County. After the Modoc Sheriff’s Office retrieved the bones, they were sent to a California DoJ evidentiary lab in Chico to be analyzed and tested and were eventually determined to belong to Nick.

Craig wasn’t notified of the remains until about three months later, after lab testing concluded. In the end, it was the dental records that she had worked so hard to acquire that allowed the skull to be identified as Nick’s.

As a cousin told Craig, without her efforts, “They wouldn’t even be able to identify him.”

A month after the skull and humerus bone were identified, the Modoc County Sheriff’s Office conducted its first official search in the area where the bones had been found. Investigators discovered additional bones — vertebrae — they believed also belonged to Nick. They notified Craig about the additional remains.

After picking up Nick’s box of remains, Craig opened the box to place a beanie, something Nick often wore, on his skull for burial. She noticed the vertebrae were missing, something which neither the mortuary nor sheriff’s office had informed her about.

She contacted the sheriff’s office and was told Nick’s vertebrae had been lost somewhere between the evidentiary lab in Chico and the sheriff’s office. An internal investigation was ongoing, the sheriff’s office told her, to find out what happened to the bones. Craig said she thinks if she hadn’t opened the box of Nick’s remains, they never would have told her the vertebrae were missing. They still haven’t been located, and it’s not clear if they were ever DNA-tested to ensure they belonged to Nick.

“I’m sick and tired of figuring out how to show these guys how to do their job,” Craig said. “My frustration is the only thing that’s pushing me.”

Dowdy did not answer specific questions from Shasta Scout about the missing vertebrae, instead responding vaguely that “continued investigative efforts will bring clarity to these concerns in due time.”

Despite Nick being found, the challenge continues

As a member of the Pit River Tribe, Craig had specific needs and concerns when it came to handling Nick’s remains. She said her Tribe believes that the deceased need to be buried quickly in order to travel to the next life. Because she wasn’t allowed to pick up Nick’s remains until this past May, more than a year after they were found, she worried that his spirit was stuck between here and the next life. This was another source of intense emotional distress.

“There’s been nothing at all I can control during this whole thing,” she said. “That was kind of one of the things that I thought I could.”

Noting his own tribal affiliation, Modoc Sheriff Dowdy said that he has approached the case with “great care and reverence” but did not explain why it took so long for Craig to get access to Nick’s remains for burial.

“Once specific Native American customs were brought to our attention,” Dowdy wrote, “we acted promptly and respectfully to ensure those traditions were honored.”

Nick’s cause of death still hasn’t been officially determined. For various reasons, Craig said she thinks her son was murdered, though law enforcement hasn’t shared any evidence to back that idea.

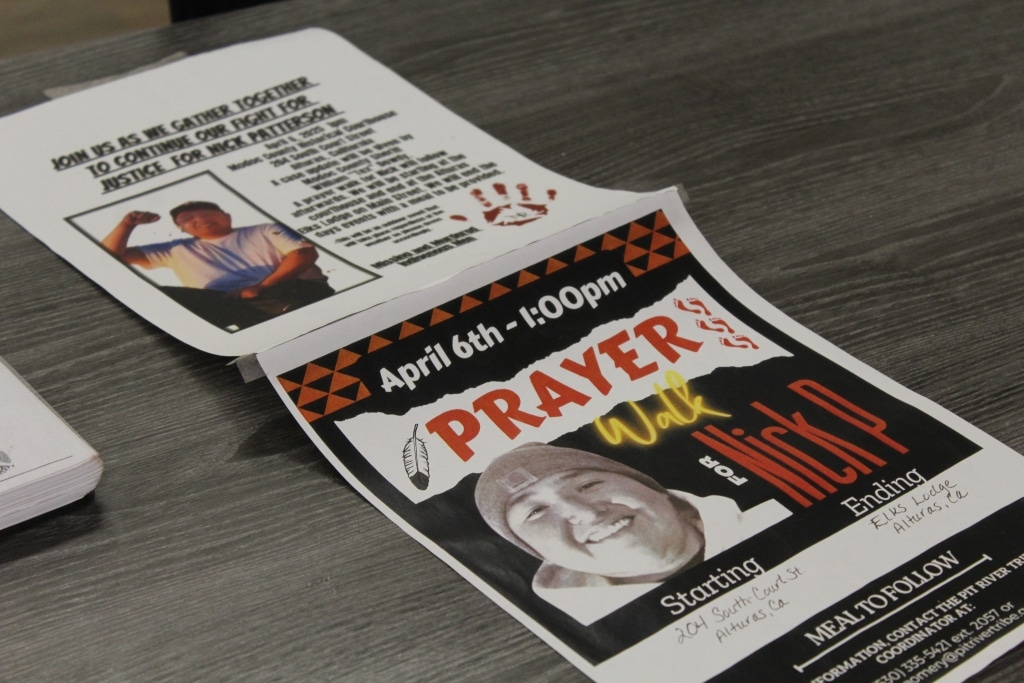

In late June, dissatisfied with the Modoc Sheriff’s Office’s prior efforts, Craig organized a grid search to try to look for more of Nick’s remains. About 20 people were involved, including family, members of the Pit River Tribe and the Modoc County Sheriff’s Office. The search went on for around seven hours, and cadaver dogs were used to try to find human remains. A few bones were found, but they still need to be tested to see if they’re human.

Amanda Geopfert, a member of the Madesi band of the Pit River Tribe who attended the search for additional bones, said the mishandling of Nick’s remains has reinforced her belief that law enforcement hasn’t done enough for his case.

“I feel like every step of the way, the system has failed their family and failed Nick, even as far as losing his remains,” Geopfert said.

Craig said she was glad to see the search happen because it reinforced her belief in the community’s continued support for Nick.

“It’s awesome to see everybody still interested in the case, still wanting to know what happened, where he’s at,” Craig said. “That helps me. He hasn’t been forgotten, and it’s still an issue.”

Craig’s process through grief and growth

Over the five years since Nick went missing, his case has taken over Craig’s life. But it’s also been a major learning experience for her, she said. Not only has she navigated records requests, DNA sampling and communication with officials and experts, but she’s also had to learn how to be there for her family in new ways. She said she’s been careful not to overshare information about certain details in Nick’s case to avoid traumatizing or disturbing family members. And she’s also had to learn to not act on emotions.

“With this, I have to make sure that when my daughter calls, that I’m not freaking out and being all upset because I have to be there for her,” Craig said. “I have to be able to do stuff like this.”

She feels like the process has affected her very perception of time.

“It feels like it was just the other day that he first went missing, and sometimes it feels forever and ever,” she said. “I’ve never missed anything so much in my entire life.”

Not long after Nick disappeared, Craig said she met with a psychic to learn more about his disappearance. Since then, she said Nick’s spirit visited her in the times she’s needed him most. The first time she saw him, she said he told her that if she wants to see him again, then she has to go where he’s at — a sign to her that he’s passed into the afterlife.

She said seeing Nick’s spirit has been a helpful part of the mourning process.

“At first, I didn’t understand why this had to be such a long, drawn-out process, why we’ve had to do everything we’ve done,” she said. “But I do know now that if I would have found everything the first couple weeks, it would have been too much for me.”

A piece of a complex crisis

Indigenous people go missing at a higher rate than the general population and are more likely to be victims of violent crime. Northern California has been identified by researchers as an epicenter of the MMIP crisis, ranking among the top areas of the country for missing and murdered Indigenous people.

After attending several MMIP conferences over the years and doing in-depth research, Craig said she’s been able to observe up-close how deep and complex the crisis truly is. She considers herself among the lucky ones because she has at least some answers.

“There’s families out there that can’t even file a missing persons report because law enforcement won’t listen to them, or they’re being threatened,” she said. “Remaining grateful and thankful for the stuff that I do have is something I gotta remind myself of constantly. There’s been a lot done in [Nick’s] name. He’s doing good things for people, and he’s not even here still.”

Madison Holcomb is a recent graduate of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She’s reporting for Shasta Scout as a 2025 summer intern with support from the Nonprofit Newsroom Internship Program created by The Scripps Howard Fund and the Institute for Nonprofit News.

Do you have a correction to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org.

Comments (5)

Comments are closed.

Shasta County Sheriff’s Office put more expedient effort into hunting down a little girl’s goat than they did for Nick.

Terrible story! Has there been discussion of what LE should do from here and what needs to be done for serious problems that exist? I have been through this exact type of missing person in Hawaii. He was never found.

This is such a heartbreaking story. One question I have is, who was the Sheriff when this happened? There are several questions in this article that I think require an explanation from the Sheriff regarding their actions, such as why they did not search with dogs.

Barb: The current sheriff is always responsible to answer the media’s questions and respond to the family of victims, regardless of when cases occurred. As you can see from our story, we received little response from the sheriff in response to our specific questions.

Thank you so much to Madison Holcomb a recent graduate of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The reporter for Shasta Scout as a 2025 summer intern with support from the Nonprofit Newsroom Internship Program created by The Scripps Howard Fund and the Institute for Nonprofit News.

To the MOM of Nick Patterson and the rest of the immediate family, close family members and friends. I just want to say that NICK PATTERSON will always be remembered. Yes some families do not get the same outcome, actually a lot of families do not. For you to find your way thru all the grief that I know can be very overwhelming and very heart breaking. Just know we support you. The Boys& Us love always-The Baby sister of a Murdered Brother!