Shasta County Poised To Provide Inspiration To California Educators Seeking To Implement New Statewide Indian Education Act

A state law passed last fall encourages districts to develop culturally appropriate history lessons. The groundbreaking work of Shasta County’s American Indian Advisory (AIA) is providing a model for districts seeking to implement the new law statewide. Now an additional $1.1 million in grant funds will take the AIA’s work even further.

1.22.23 10:45 am We have updated this article to correct a misspelled Tribal affiliation.

In the 1970’s, Redding Rancheria Chairman Jack Potter says he was sent to speech therapy because his Shasta County teachers thought there was something wrong with his pronunciation.

Potter was actually speaking a legitimate dialect, sometimes described by linguists as American Indian English, that he had picked up from his grandparents and other elders in his life. Through speech therapy, Potter learned the “correct” way to speak, a process that caused new distress and confusion when he realized he now spoke noticeably differently than his elders did.

He shared this personal story at a State Assembly Education Committee hearing in the fall of 2021, as part of his explanation for why he dropped out of school when he was only in 7th grade.

“I just couldn’t take the abuse, the lack of belief in our ways and our traditions,” Potter said.

That hearing, which focused on Native American curriculum and student supports, helped spur AB 1703, also known as the California Indian Education Act, which became California law last fall.

The bill is intended to support improving the scholastic achievement of Native students and ensure all students are provided accurate information about the history and culture of California’s diverse Indigenous peoples.

Potter and Shasta County Office of Education (SCOE) Superintendent Judy Flores were invited to the 2021 hearing to discuss the work of the American Indian Advisory, a collaboration between Shasta County educators and local Tribes that began in 2018 as part of Flores’ efforts to improve outcomes for Native students. Flores’ groundbreaking collaboration has already led to changes in state law that protect Native students’ rights to attend cultural ceremonies as an excused absence from school.

Now SCOE officials say educators from other school districts have begun contacting the American Indian Advisory group in connection with California’s new Indian Education Law, which encourages school districts to create task forces with local Tribes to develop curricula about Tribal histories, cultures and governments. Local task forces, like the American Indian Advisory, will help other regions by submitting reports to the state Department of Education that help the state develop models for curricula and policies.

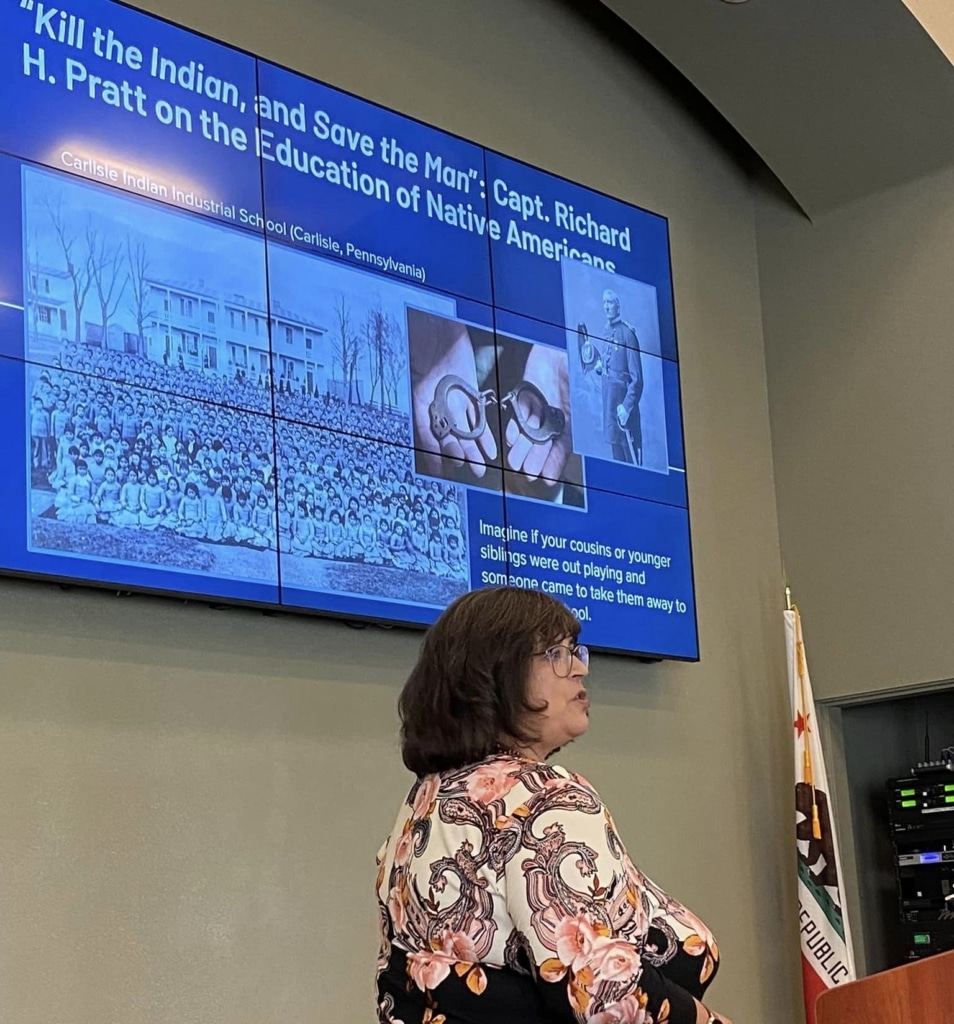

Schools became sources of trauma for local Native families during the inception of Indian Boarding Schools in the late 19th century. Today, Native students continue to endure traumatic and discriminatory experiences, making building trust between Tribes and local educators a challenging and time-consuming process.

Nineteen local teachers are now participating in some way in the American Indian Advisory’s development of new curriculum that includes the histories, cultures, and experiences of local Tribes. That development process includes consistent consultation with representatives from the local Tribes. “It’s a long process, but it’s the right thing to do,” said Cindy Hogue, who is Dawnom Wintu and a longtime Shasta County middle school teacher. “We rely on (the Tribal representatives’) wisdom.”

At a time that’s rife with angst and misinformation about what’s being taught in local schools, Hogue said the fact that so many teachers are working on the Tribal curricula speaks to the demand among educators for the tools and resources to teach more diverse histories.

“They’re thrilled, especially our primary school teachers,” Hogue said. “Many of them have Pit River and Wintu children in their classroom but didn’t know how to teach about the local Tribes.”

Curricula are currently being developed for third, fourth, fifth and eighth grades, and there are plans to create lessons for other grades in future, Hogue said. While the lessons won’t shy away from the painful histories of colonization and discrimination, SCOE’s Director of School and District Support Kelly Rizzi said the lessons will emphasize “resilience, the beauty of their cultures and the opportunities we have to learn from them.”

Educators also expect that Native students will perform better scholastically when their Tribes and cultures are honored in the curriculum.

“What we’re after is inclusion,” Hogue said. “We really want Native students to see themselves as part of the narrative. . . I want my own kid to feel like he’s important and doesn’t have to hide who he is (at school).”

The curriculum will also provide a unique opportunity for Native and non-Native students alike to learn a richer and more complex history of where they live, according to Rose Soza War Soldier, an enrolled member of Soboba Band of Luiseño Indians and an Assistant Professor of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State.

Soza War Soldier said it’s important that students learn about local Tribes because of their unique cultural, religious and political ties to their ancestral lands. Curriculum, such as that being developed by SCOE, can help residents understand the contemporary activism, challenges and advocacy of local Tribes, who often are ignored in school textbooks, she said.

“As someone who went through the public school system, I remember we learned about Indians after we learned about dinosaurs. The structure of the timeline was revealing to me,” said Soza War Soldier, who grew up in Davis. “There is a tendency to not see Native people as contemporary people, that we’re living and breathing and it’s important students recognize we’re still around today.”

“As someone who went through the public school system, I remember we learned about Indians after we learned about dinosaurs. The structure of the timeline was revealing to me. There is a tendency to not see Native people as contemporary people, that we’re living and breathing and it’s important students recognize we’re still around today.”

Rose Soza War Soldier

New $1.1 Million Grant will Increase Impact of American Indian Advisory

SCOE will continue to expand on the American Indian Advisory’s work after receiving a three-year, $1.1 million grant from the state to pursue a project known as Learning Communities for Native Success. Funds will be used in part to increase graduation rates and attendance for Native students while reducing negative outcomes like suspensions or expulsions, said Hogue, who is the coordinator for the grant.

Funds are also being used to create Native-centered extracurricular educational opportunities for all students. SCOE will also hire two community connectors dedicated to supporting the basic needs of Native students and families with community resources. The new community connectors will work specifically with Native families in a sensitive and effective manner, Rizzi said. They’ll join twelve other community connectors already serving diverse students in local schools.

The grant will also provide restorative justice training for most of Shasta County’s school districts, especially those that serve Native students. Restorative justice models, which include talking circles and chats, Rizzi said, are used as alternatives to punitive strategies and provide teachers the care and tools to address the underlying causes of disruptive student behavior. This shift in strategy away from traditional discipline such as expulsions and suspensions is likely to especially benefit Native students. A 2019 comprehensive study found that Native students suffer disproportionately high suspension and expulsion rates in public schools both locally and throughout the state, largely due to institutional biases.

The “endgame” of the grant, Hogue said, is to ensure that schools become a place where Native students can thrive in their identities and be respected for who they are. “We want students to be in school and we want them to graduate,” Hogue said. “That way they are going to contribute to the community at large but also become the next generation of Native leaders.”

Annelise Pierce contributed to this story.

Learn more about how we cover Indigenous Affairs here. Submit a correction here. Have a comment or question? Email us: editor@shastascout.org

Related coverage: