Shasta County Work Training Changed His Life. When His Program Lost Funding, He Lost Hope.

After three years of job training and paychecks, Shasta County resident Travis Gregorio was given only three days notice that he would no longer receive services through the County’s Opportunity Center. Gregorio, who has significant mental health disabilities, now faces an uncertain future.

2.11.2023 5:25 pm: This story has been updated to correct a few biographical details as well as specifics related to communication between Gregorio’s family and the County.

Editor’s Note: This story includes references to attempted suicide. Please read with care. If you need mental health support or are feeling hopeless or suicidal, text or call 988 for help. Significant time and care were taken to ensure our sources informed consent in the reporting and publication of this complex and personal story.

For the last three years, Travis Gregorio, age 24, held a job at Shasta County’s Opportunity Center, a government-funded work training program that has been run by the County since 1964.

Under a client contract with the Opportunity Center (OC), Gregorio was paid minimum wage to provide janitorial services, including emptying the trash and cleaning bathrooms and floors, as part of a program designed to allow him and others with disabilities to gain job experience in a supervised setting.

Diagnosed at a young age with autism and ADHD as well as other mental health challenges, Gregorio spent much of his youth in and out of group treatment homes. His behavior, he says, is often difficult to predict, even for himself. When angry, he sometimes acts out with aggression, likely because his executive function disorders cause a significant lack of impulse control.

That aggressive behavior was what led Gregorio to leave home at age 18, because he feared that his unpredictable behaviors could harm his family. His mental health disabilities also made finding and keeping employment impossible, his mother Susan Power says, leaving him homeless on and off over the next three years.

At twenty-one, Gregorio’s parents were able to help him apply for a job through the Department of Rehabilitation (DOR), which referred him to the work training program at the Opportunity Center. As a client there, Gregorio wasn’t traditionally employed; instead mental health funding allowed him to be paid minimum wage while working under staff supervision that included feedback about his behaviors.

That supervision and feedback have been crucially important for him, Gregorio says, because he has trouble anticipating his own behaviors early enough to stop them.

“I just do things unexpectedly,” he said, “like I might just kick a door open. I’m not even mad when I do it, I just don’t think about it. But it’s not good for keeping a job.”

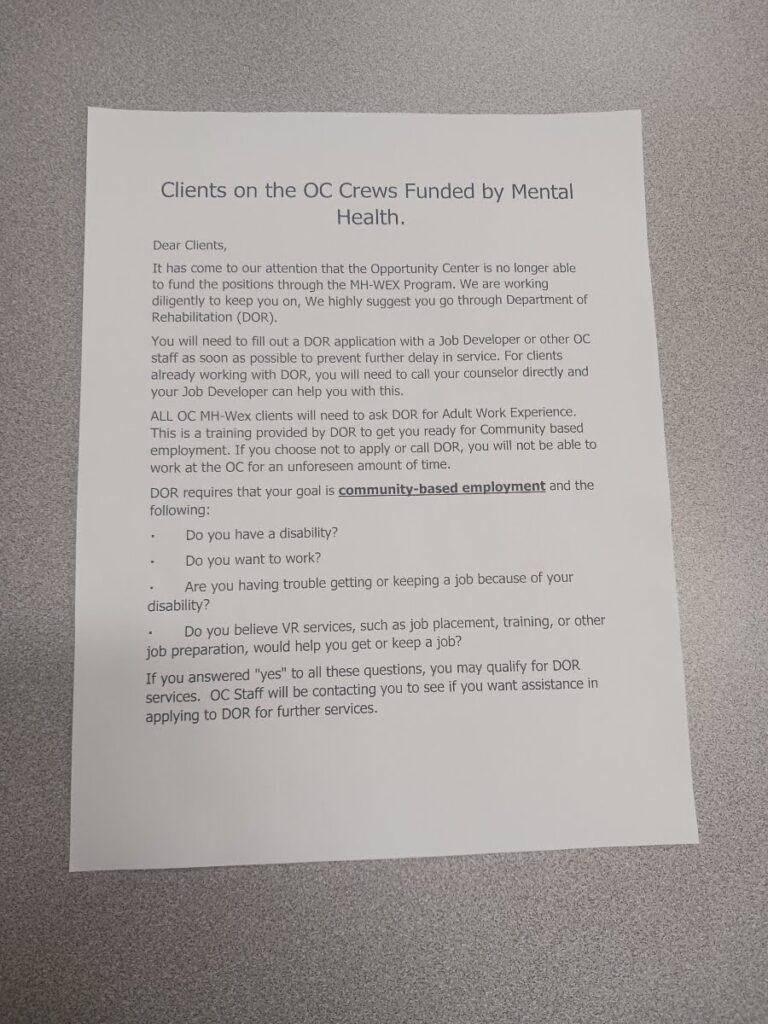

Gregorio says he had hoped to work at the Opportunity Center for two more years, but on Tuesday, January 25, just before starting work, Gregorio says he was pulled into one of the Center’s offices along with several of his coworkers.

There, he recounts, the Acting Director of the Opportunity Center, Jacob Lingle, told him and the others that funding for the specific program that paid for his services was running out, and that he would only have three more days in the program before losing his services.

Gregorio said staff helped him apply online with Department of Rehabilitation, which had referred him to the Opportunity Center three years earlier and told to call frequently to follow up.

Gregorio spoke to Shasta Scout a few weeks ago, on Wednesday, January 25th, in a private room at the Redding Library, stoically answering questions about paperwork he had received from the Opportunity Center, his monthly budget, and how his rapid change in employment might affect his living situation.

He described himself as feeling “numb” after learning the day before that he would only be employed for three more days. Asked if he was in shock, he spoke with characteristic straightforwardness.

“My therapist says it’s not really shock,” he said, “I’m just readjusting.”

But while Gregorio was calm, he also expressed significant uncertainty and concern about his future, particularly how he would be able to afford rent while waiting for his referral to the Department of Rehabilitation to be finalized. His regular paychecks significantly reduce the amount he receives in Social Security Income, to only $400 a month. Without employment his Social Security Income payments will increase but the change in benefits are likely to take 2-3 months.

Gregorio worried about how he would pay his bills during that time even though his predictable expenses are low, just $800/month to stay with others in a local cooperative living situation managed by Promise Homes . . . and $133 for his phone.

Like all Opportunity Center clients, Travis had faced an uncertain future with the program even before his three-day notice. Over the last few months, Shasta County Supervisors have been evaluating the Opportunity Center’s operational efficiency. They’re considering moving the program under the ownership of a nonprofit service provider, but significant concerns from parents and clients about how that transition might affect those, like Gregorio, who are employed by the Opportunity Center, have so far delayed a decision.

A statement about the Opportunity Center on the County’s website says any upcoming changes will be accomplished “with the smoothest transition possible, or no transition at all” to avoid harming clients.

“Protecting the wellbeing of this vulnerable population,” the site says, “remains the top priority for the Board of Supervisors.”

Operating costs for the OC have periodically exceeded revenues, depleting OC fund reserves. Without these reserves the OC will eventually need to reduce their services. Protecting the wellbeing of this vulnerable population remains the top priority for the Board of Supervisors. They seek to provide OC clients with the smoothest transition possible, or no transition at all.

Shasta County

But for Gregorio’s mother Power, the way the County handled the timing and communication around her son’s change in services hasn’t appropriately prioritized his protection, given the County’s awareness of his significant mental health disabilities.

Shasta Scout reached out to the county’s Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA) repeatedly over the last several weeks with questions about why the changes in Gregorio’s services occurred so abruptly and how they were communicated.

In response to multiple phone calls and emails, Amy Koslosky, a Supervising Community Education Specialist with the County, wrote by email that Gregorio and a few other clients services were funded by a federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMSA) grant.

In response to follow up questions she explained that the County recently realized that SAMSA funding for Opportunity Center clients had been exhausted in September 2022, more than four months ago. That discovery appears to be what pushed the County to abruptly terminate Opportunity Center services for Gregorio and six other clients.

Koslosky emphasized that the Opportunity Center was not closing, writing “no one is losing services completely,” and all clients are being referred from “one unfunded program to a different funded program.”

Koslosky provided no information about what other funded County, state or federal programs Gregorio might qualify for, other than the Department of Rehabilitation. She acknowledged that the County has no control over how quickly the Department of Rehabilitation might respond to Gregorio’s employment need, saying that clients had been informed they may experience a “small gap” in services as the Opportunity Center finds and obtains new funding sources.

‘The goal now,” Koslosky wrote vaguely, “is to move clients into programs that transition clients into the community.”

“This is a routine transition,” she emphasized.

It may be a routine transition for the County, Power says, but the sudden loss of stable employment through the OC has been anything but routine for her son. That’s why she and her husband, John Gregorio, spent the next few days after Gregorio was given notice trying to make contact with HHSA’s Director, Laura Burch, and the County program director for the Opportunity Center, Julie Hope, to learn why clients had been informed only three days before the transition and why they had not received more careful communication of the process, given their known mental health challenges.

Power says Hope told her husband, John Gregorio, that the process of sharing the change in funding with clients had gone well.

“She said it went really smoothly. The clients were okay with it,” Power paraphrased.

That did not reassure Power, who was supporting her son in real time through what was an obviously difficult transition. She was most concerned with how the transition was communicated to her son, whose mental health disabilities make self advocacy in a setting like a job termination, very difficult.

“He has a brilliant mind,” Power said, “and poor verbal skills. If someone is talking to him he’s not going to process what was said — it’s really not cool that they’re just handing him stuff.”

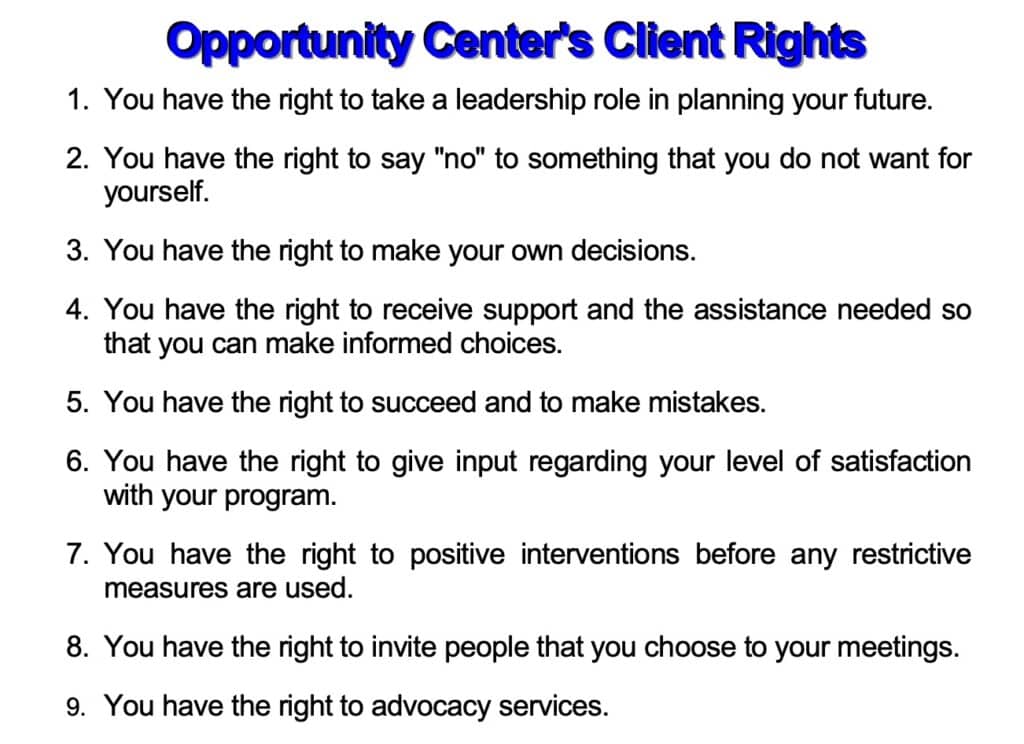

The process also appears to be out of alignment with the Opportunity’s Center’s organization’s principles for how to handle client interactions.

According to the Center’s Client Rights handbook, Gregorio should have been able to “take a leadership role” in planning his future and “receive support and assistance to make informed choices.”

Asked by Shasta Scout if he felt he had access to those rights during his transition from the OC, Gregorio slowly shook his head no before dropping his gaze and sighing.

On Friday, January 27, just three days after being told he was losing his services and his job, Travis showed up for his last day of work at the Opportunity Center.

After a few hours, he was told he could leave work early, another small change in the predictability of his routine that added to his distress, Power says. That night he called her, feeling more hopeless than before, with a plan to overdose on one of his medications.

Power called 911, but by the time first responders arrived Gregorio had already left home. He was found, some hours later, not far from his home in critical condition. He was admitted to a local intensive care unit where he remained critical for several days before slowly recovering from his overdose.

Power says the way he responded to his loss of employment was predictable, given his known mental health needs, and the central importance of his job to his ongoing stability. Having had more time to adjust to the change in employment, she says, and better communication about what was happening and how he would be supported would likely have made the difference he needed to stay safe.

Before his job at the Opportunity Center, Power says, her son lived only in the moment, thinking about his next meal and where to sleep. His employment had given him enough stability and security to think about the future, she says, explaining that Gregorio hopes to help others benefit from his difficult life experiences by someday becoming a social worker.

“He often spends hundreds of dollars from his paycheck each month on food for his friends in the unhoused community,” Power said. “He likes to help people.”

Last week, Gregorio was well enough to meet with Shasta Scout at the Redding Library again. He said he’s recovering well physically but is struggling mentally and emotionally, worried about his loss of employment as well as the loss of his phone, which was left behind on the street by first responders when he was transported to the hospital.

He expressed ongoing feelings of hopelessness. With only one more paycheck from the Opportunity Center coming and a 2–3 month gap before his social security benefits will increase, Gregorio says he won’t be able to pay rent next month.

He plans to buy a sleeping bag and some tarps and move back to the streets.

This is a developing story.

Do you have a correction to this story? You can submit it here. Do you have information to share? Email us: editor@shastascout.org